The oldest written source dealing with the Çanakkale region, known as Troas in antiquity, is the works of Homer. The Iliad, believed to have been transcribed by Homer, who was born in İzmir (ancient Smyrna) approximately 2700 years ago, also uniquely describes the geography extending from Mount Ida to the shores of the Sea of Marmara. Although researchers do not agree on whether Homer visited this geography, which he described in great detail with its mountains, rivers, flowers, and animals, the details in the narratives reveal that our poet knew this geography like the back of his hand.

Another important written source about the region after Homer is Herodotus of Bodrum (Halikarnassos), considered the father of history. This famous historian provides information about the cities in the Troas Region in his work. With the information our historian provides, we learn why and by which famous commanders the region was visited. In Herodotus's history book, the Troas Region is particularly described with the backdrop of Trojan mythology and the epic of the Trojan War. In this context, the ancient city of Troy, or Ilion by its second name, is the most important center of the region both historically and mythologically. In fact, it is not known exactly when Troy, also known as Ilion, began to be identified with the Trojan War in antiquity, but we understand that this view has been transmitted at least until the 5th century BC, from Xerxes' visit to Troy during his campaign to the West in 480 BC. The Persian king, who set out to rule the world of that period, visits Troy before invading the Western lands, i.e., the Greek homeland, from the Eastern lands and sacrifices 1000 cows in that "sacred place." Herodotus writes the following about this visit:

"The army had reached the river Skamandros; since they set out from Sardis, they first experienced a shortage of water, unable to find enough water for the soldiers and animals. When they reached this river, Xerxes climbed the hill where Priamos Pergamon was located, wanting to view the surroundings. He viewed it, listened to the famous events that took place there, and sacrificed a thousand unborn cows for Ilion Athena, while the priests (Magiers) sprinkled water on this land of heroes. After these ceremonies were completed, a night terror threw the camp into chaos. At dawn, they set out, taking the cities of Rhoiteion, Ophryneion, and Dardanos (the latter was in Abydos territory) to the left and the Gergiths, descendants of the Trojans, to the right" (Herodotus VII 43).

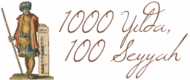

This visit points to a very important issue regarding the location of Troy: Troy is located at the easiest crossing point between Europe and Asia, and therefore it can be considered as belonging to both the West and the East. From the care Xerxes showed to this place, it can be inferred that he considered the Trojans as Asians, i.e., Easterners.

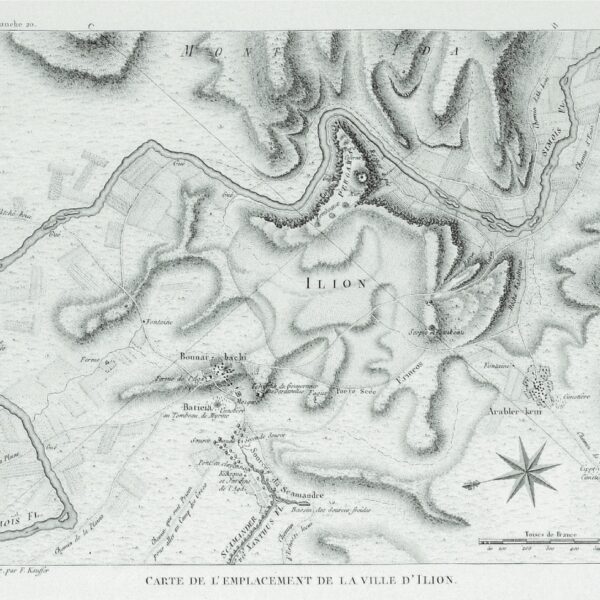

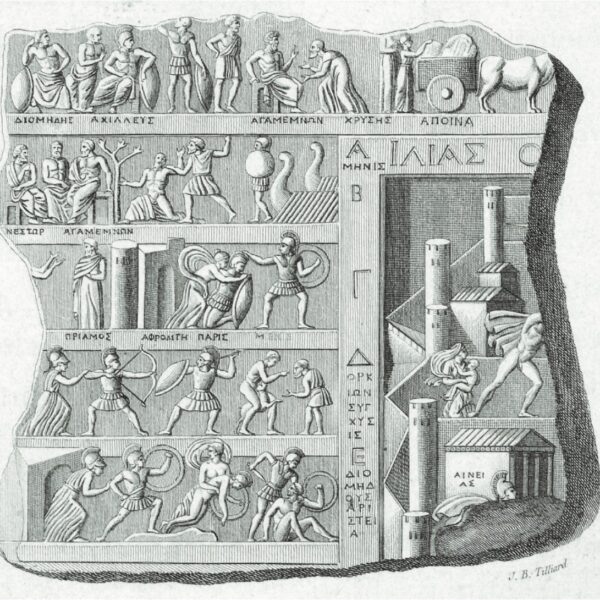

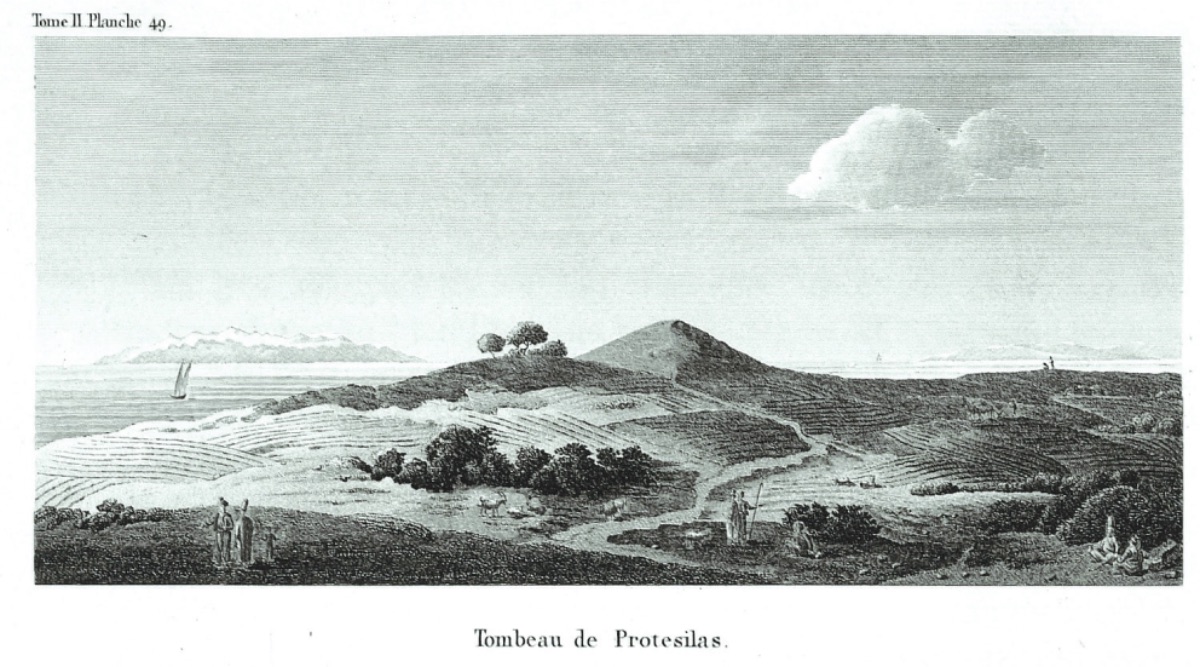

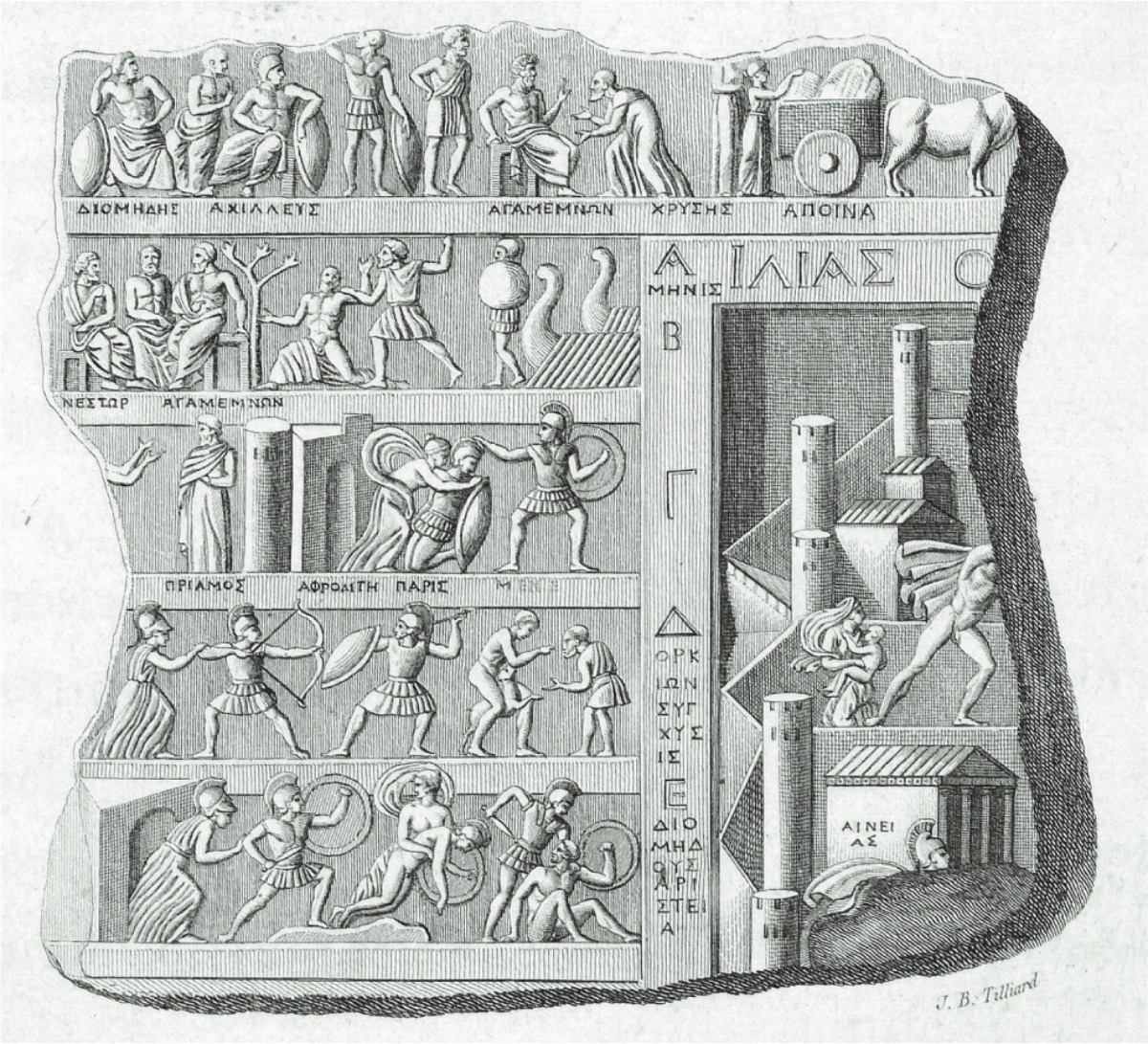

But years later, the Persians are defeated by the Macedonian Alexander the Great. The famous Roman historian Arrian describes in detail the sentimental journey of Alexander the Great to these sacred lands in 334 BC. After sacrificing at the tomb of Protesilaos on the Gallipoli Peninsula, Alexander crosses the Dardanelles from West to East and arrives at the plain of Troy. After ascending to Ilion, he sacrifices at the temple of Athena and offers libations for the heroes. He then hangs his weapons in the temple of the main goddess and takes some of the weapons that have been preserved since the Trojan War. His respect for these weapons is so great that he carries them with him on his Eastern campaign. Alexander the Great dies before he can fulfill his promise to make Troy a magnificent city again. However, in the 300s BC, many other wealthy individuals make significant financial contributions to the development and prosperity of the city. As a result, large-scale construction works are carried out in the city. A new Athena Temple is built in Ilion, with scenes depicting the war between the Achaeans and the Trojans on its front. To the north of the city, a large theater with a capacity of about 8000 people is built (Theater A). Sacrifices are offered to Trojan heroes in the Athena temple, duels representing the Trojan War are held in the agora, the city's center, and plays about Troy are performed in the theater. During this period, Troy clearly turns towards the West.

The magnificent Late Bronze Age defensive wall to the south of the mound was repaired or partially rebuilt in the 250s BC. This wall was also considered proof that Ilion was Troy at that time. The agora, the city's center in Ilion, was located immediately south of the Troya VI defensive wall. When we accept Greek Ilion as identical to Homer's Troy, the restored Troya VI defensive wall provided an ideal backdrop during the staging of Homer's epics.

In the second half of the 3rd century BC, Ilion's feature as a tourist destination increased significantly. Because Ilion began to be accepted as the main city of the Romans. According to the epic about the only surviving Trojan hero Aeneas migrating to Italy via the Mediterranean after the Trojan War, Aeneas fights a second war in Italy, establishes a new city, and thus gains the feature of being the ancestor of the Romans. This epic, which revives the Trojan epics in people's minds, causes a large number of people to visit Troy intensely. As a result, Troy begins to become a prosperous city. The sacred area west of Troy is expanded, and two more new temples are built. A new council building is also constructed right at the border of the Athena Temple.

However, in 85 BC, as a result of internal conflicts in the Roman Empire, the rebellious commander Flavius Fimbria attacks Ilion and destroys the city. The Athena temple, the sacred area in the west, and the theater are largely destroyed. Immediately after this attack, the Roman commander Sulla visits the city to assess the damage and promises a large financial aid to the Ilionians. The city even changes its new year calendar in honor of his visit, aligning the new year with the day Sulla visited the city. But the promised money never arrives.

The famous emperor Julius Caesar, who comes from the Julier lineage, which traces its origins to Aeneas, also comes to Troy to see the sacred lands. Caesar accepts the city of Troy as the city of his ancestors, and on the coins he minted, there are images of both Aeneas and his father Anchises. Like Sulla, Caesar also promises aid, but this promise is not kept either.

The very poor economic situation of Troy changes during the reign of the Roman emperor Augustus. When Augustus visits Troy in 20 BC, the city is on the verge of becoming a ruin.

On the coins from the Roman period, scenes from the Trojan War, which the Romans were very interested in, appear; such as Aeneas, Hector, and Priamos. Especially during this period, Ilion markets itself as Homer's Troy and tries to attract wealthy tourists from the nearby new Roman colony city of Alexandria Troas.

The famous geographer Strabon, born in Amasya (Amaseia), describes Troy and its surroundings in great detail in his work Geography, which is estimated to have been written in 18-19 AD:

"No trace remains of the ancient city. This is very natural. All the cities in the vicinity have been plundered, but not completely destroyed. However, it has been completely destroyed by taking all the stones for the reconstruction of others." (Strabon, Book 13.37).

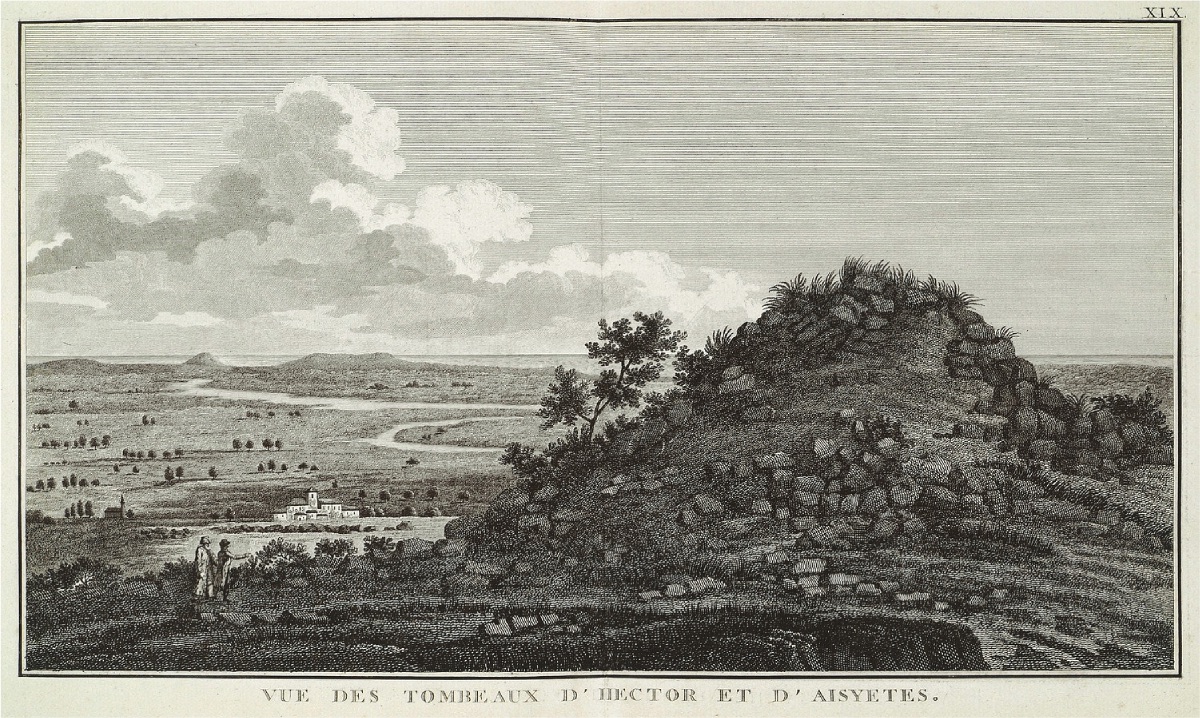

One of the emperors who later visited Troy was Hadrian. Emperor Hadrian visited Ilion in 124 AD. He first restored the tomb (tumulus) of Ajax. The stage building of the odeion is dedicated to Hadrian. The statue of Hadrian is the most important work adorning the stage building.

The visit of Emperor Caracalla in 214 AD also leads to the start of many construction works. The odeion is beautified. The bath buildings nearby are repaired. Like Alexander the Great, Caracalla also organizes races around the tomb of Achilles and dedicates a statue for the Greek heroes.

Tourist guides of that period, as they do today, show the places where scenes from Homer's epics took place, such as where Paris met Anchises or where Hector was killed.

When considering the history of Troy during the Greek and Roman periods, the first thing that stands out is the uninterrupted continuation of the Homeric tradition. The acceptance of the city as the site of the Trojan War is the main theme of Hellenistic Roman Ilion, and it is also the reason that attracted many Roman emperors to this city. Ancient sources indicate that at least eight emperors and their relatives visited Ilion. One of these emperors, Germanicus, even wrote a poem for Hector's tomb.

However, Ilion was destroyed again by the Goths in 267 AD. The city and the region experienced their worst economic period. But when Emperor Julian visited the city in 354 AD, the Athena temple and its statues were still standing, and tourist guides were still showing visitors the tombs of Homer's heroes.

In the 324s AD, Byzantine Emperor Constantine (Constantinus the Great) visited Ilion and initially decided on Ilion as the location for the capital he wanted to establish. The legend of Rome's founding, linked to Troy, played a role in this decision. By re-establishing the capital in Troy, the abolition of Rome would also be justified. Although construction had begun, Constantine abandoned this very important political decision because the land around Troy was not large enough for his purposes and because Byzantium was gaining increasing importance. From the mid-4th century AD, Troy gained the feature of being a bishopric center. Troy maintained its religious and political importance in later periods, but two severe earthquakes in the 5th century AD caused almost all the important buildings in the city to be destroyed. During these years, the population of Ilion decreased significantly. Although life continued in the lower city in the 6th century AD, Ilion began to become a real ruin. From this date onwards, the identification of this place with Troy began to be forgotten. The most important factor, perhaps the only reason, for this was that during the same period, Christianity had completely influenced the world of that time, and the Hagia Sophia church in Byzantium had come to the forefront as the sole center. Troy ceased to be a symbol of the Christian world and remained a symbol of ancient times, of Greece and Rome, and it began to be forgotten along with the forgotten heroism cult. After this period, although the exact location of Troy was forgotten, its name was constantly mentioned along with the Troas region.

Although graves from the 12th/13th century AD were found in the latest excavations at Troy, the settlement traces indicating this period are very weak. In other words, although life in Troy did not completely come to a halt during those times, it had significantly weakened.

The last important person mentioned in written sources to visit Troy was Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror. Kritovoulos, the historian from Gökçeada (Imbros), writes the following:

"When he came to the city of Ilion, the center of the ancient Troy continent connected to Çanakkale, he viewed and admired the remaining ruins, ancient works, and the region; he appreciated the importance it held both from the sea and the land, praised and exalted the people whom the poet Homer praised and the honorable services they performed, expressing his feelings and saying, 'God has protected and preserved me as an ally of this city and its people until now. We have defeated the enemies of the city and, despite the passing of years and ages, we have taken revenge for the many wrongs done to us Asians.'"

With these words, Troy has turned its face back to the East and has now become an Eastern city.

The city of Troy and its legend began to spread over wider geographies in the Middle Ages, taking deep and lasting roots in European history. In this influence, especially the interest of the Romans in Vergil's Aeneas epic, the Trojan legend, and its heroes played a major role. The effect transmitted from generation to generation with Homer was further reinforced by another poet adding a somewhat political feature to the epic (Vergil's Aeneas epic). Many tribes and peoples in Europe, taking the Romans as an example, created genealogies that guaranteed them a noble past and linked their ancestors to the Trojans. The origins of many other nations, such as the English, Germans, Poles, and Turks, were linked to the Trojans.

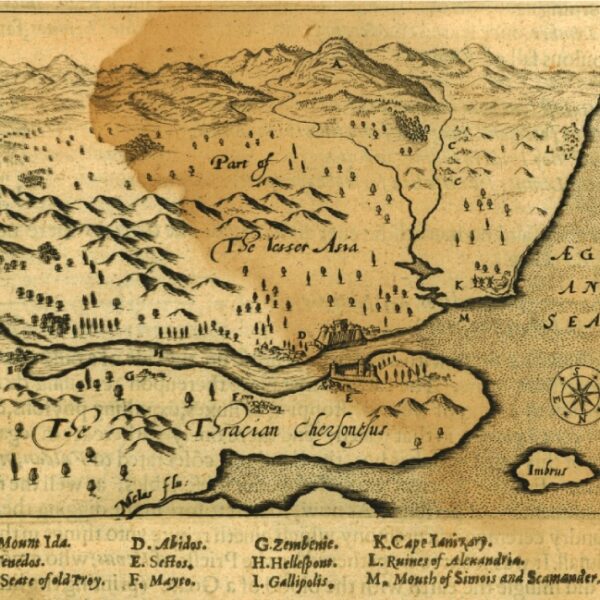

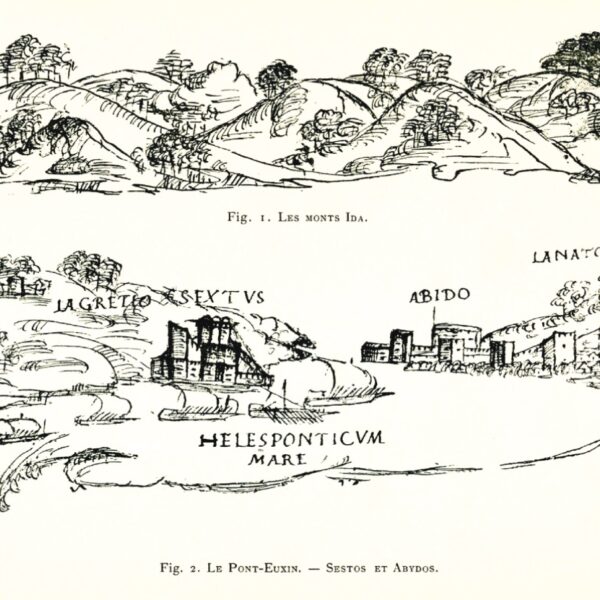

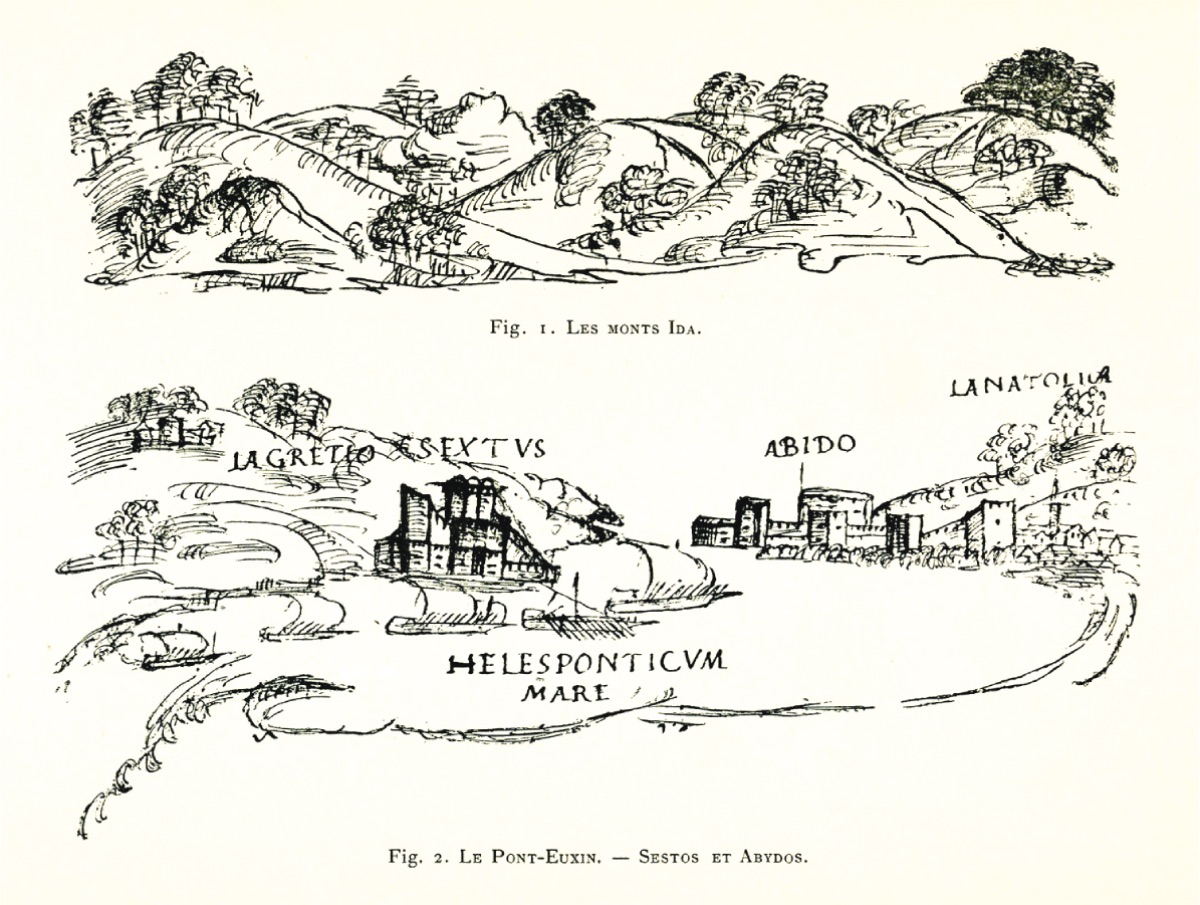

The Franks traced their lineage to Francius, the son of Priamos, and the English to Brito (Briten), the grandson of Aeneas. From at least the 15th century onwards, an attempt was made to establish a relationship between Turci and Teucri. Numerous Troy novels written in French, Spanish, Italian, German, Latin, and Greek, based on this background, swept through medieval culture. The world maps of that period were also influenced by this. For example, Troy is marked on the Hereford map of 1290 or the Andreas Walsperger map of 1448. However, its location is shown inland rather than on the coast. The reason for this is the belief that Troy was at the source of the Skamander (Karamenderes) river.

However, as we mentioned above, from the 6th century AD onwards, the localization of Troy, which began to fade, turned these visits to Troy into a kind of search for Troy.

In 1103, the English merchant and traveler Seawulf, on his journey to reach the holy lands (Jerusalem), passed through Istanbul (Constantinople) and reached Bozcaada (Tenedos) and wrote the following:

"Near the coast of the Roman Empire, there was a very ancient and famous city called Troy. The Greeks told me that the remnants of the buildings of this city were scattered over an area of several miles."

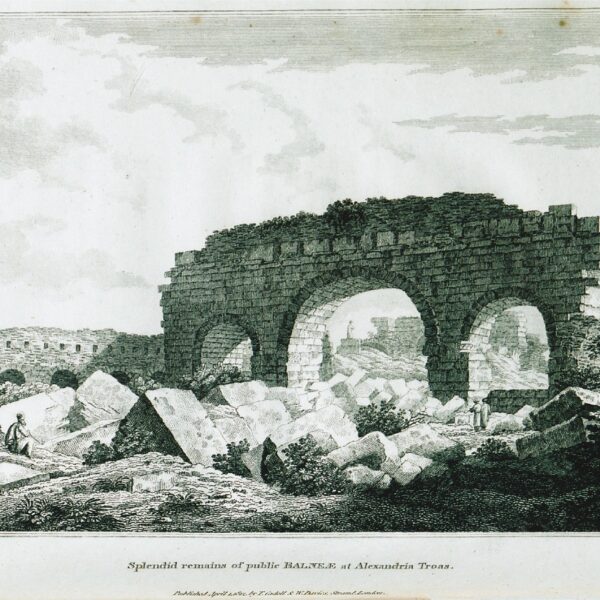

The name Tenedos, unchanged since Homer, became the most important starting point for many, like Seawulf, in the search for Troy. Homer also described Troy as the island opposite Tenedos in the Iliad's location descriptions. Therefore, this starting point also became the starting point of a misconception. As Seawulf described, Alexandria Troas, established during the Roman Imperial Age right across from the island, was accepted as Homer's Troy.

"Here they (the Greeks) established three large channels between themselves and the Trojans. The purpose of these channels was to prevent the Trojans from attacking their ships. These three channels were dug side by side."

From the accounts of Seawulf and other travelers, it is understood that the Greeks in the Troas region (especially those from Tenedos) believed that Alexandria Troas, established during the Roman Imperial period, was the ancient Troy. The Trojan legend was attributed to the entire Troas region. For example, the Catalan commander Ramon Muntaner, who was in Gelibolu between 1305-1309, fantastically narrates the Trojan legends:

"I am at the place where the Duke of Athena's wife, Boca Daner, was forcibly abducted by Paris, the son of King Priamos, to the island of Tenedos, five miles away from Hellespont (the Dardanelles: Çanakkale Strait), and where the castle attributed to Paris is located (Kyzikos)..."

The legends are thus spread across the entire region and time.

The envoy Gonzales Calvijo, sent by the King of Castile to Tamerlane, also anchored off the island of Tenedos in 1403 and wrote the following:

"On the right side of the strait was the city of Troy, known to everyone. From where we anchored, the remnants of the ancient city could be seen. It appeared that there were entrances at different distances in the city walls. In some places of these walls, there were towers, but these and the palace buildings were in ruins."

From Calvijo's accounts, it is understood that not only Alexandria Troas but also the Greek village at the entrance of the Dardanelles, Yenişehir, and the later established Ottoman fortress Kumkale were considered in the context of Homer's epics: Calvijo describes this situation as follows:

"Here they (the Greeks) established three large channels between themselves and the Trojans. The purpose of these channels was to prevent the Trojans from attacking their ships. These three channels were dug side by side."

The ancient ruins were also evaluated within a very large area during Calvijo's time:

"According to what is said, in ancient times, the area covered by the city of Troy extended from the entrance of the strait to Cape St Mary (Cape Baba/Lekton)."

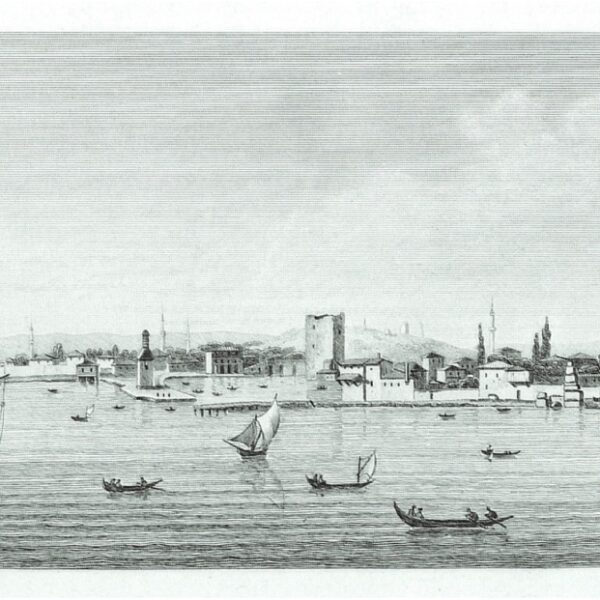

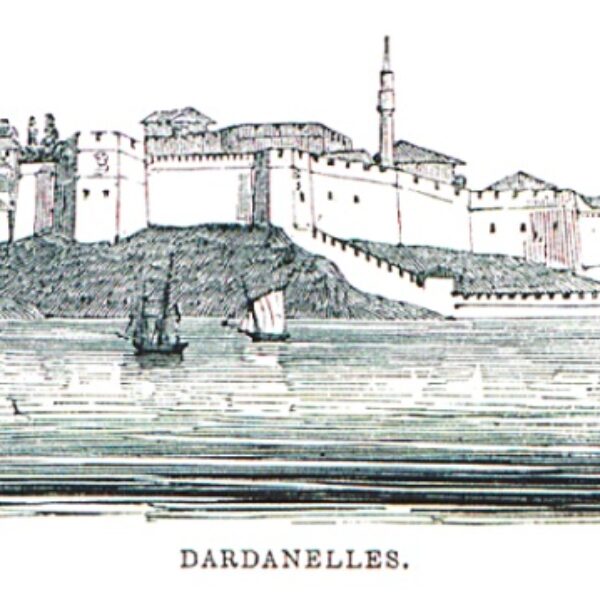

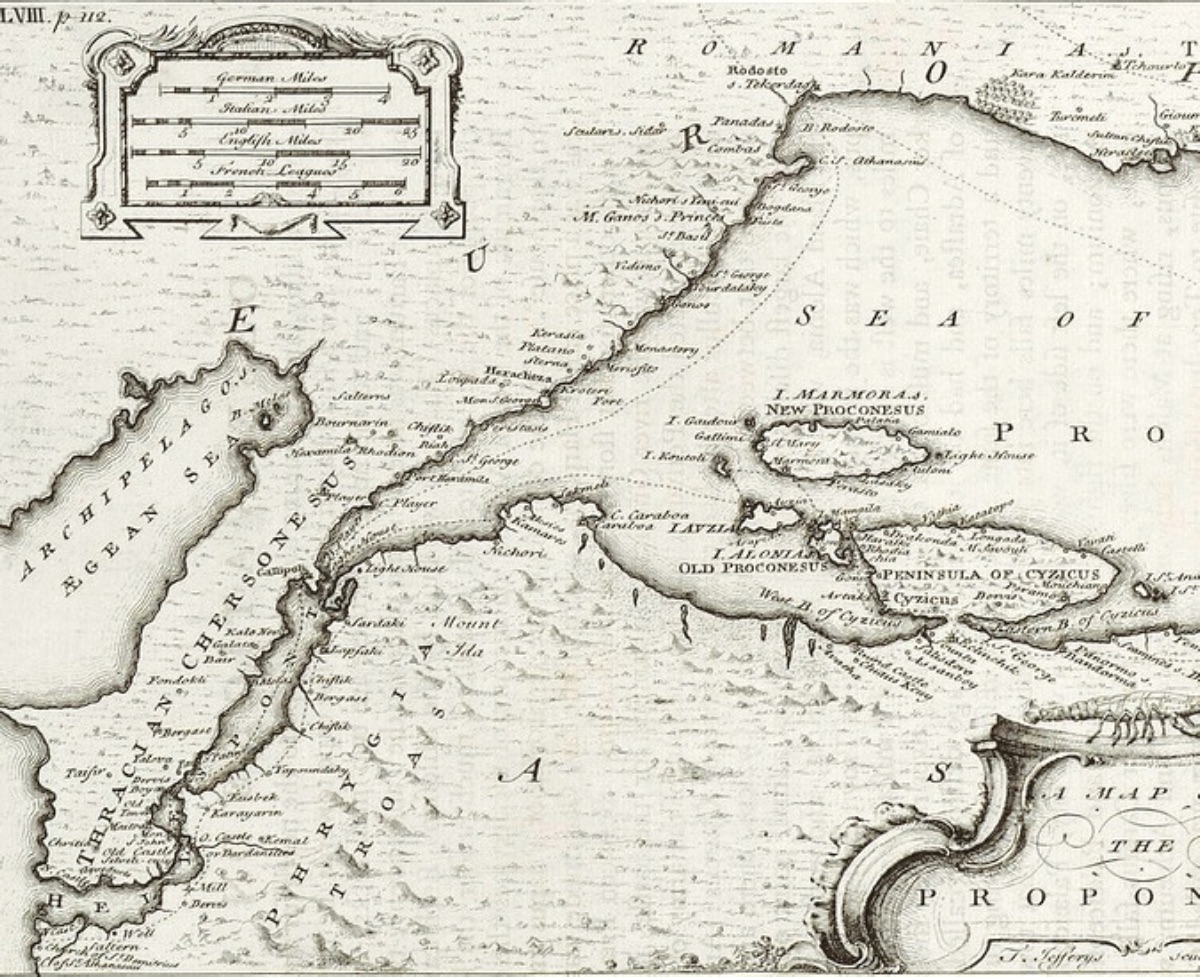

Calvijo also provides interesting information about the Dardanelles and its surroundings 610 years ago. The traveler, who passed through the Dardanelles on October 19-20, 1403, writes that the right bank of the strait belonged to the Turks, and right at the entrance of the strait, there was a large fortress and a fairly large village at its base. Calvijo writes that the fortress, with its walls in ruins and doors open, was taken from the Turks by the Genoese a year earlier and destroyed. He also mentions that the place known as the Intersection of All Roads (old Kumkale) was used by the Greeks as a headquarters to besiege Troy. According to Calvijo, the Turks began to spread into Europe via Gelibolu, the first city they conquered on the shores of the strait. Calvijo describes Gelibolu as the center from which the Turks opened to the Mediterranean with its large shipyards.

The knight and merchant from Cordoba, Pero Tafur, upon hearing what was said about Troy, set out in 1437 to see Troy from the place he called Focia Vecchia (Foça). After a two-day horseback journey, he arrives at a place that the Turks accompanying him say is Troy:

Tafur writes, "But there was no one there from whom we could get any information." Later, from what he writes, it is understood that Tafur also visited Alexandria Troas opposite Tenedos, thinking it was Ilion. His certainty that he found Troy comes from his observations made from Tenedos, where he arrived by ship: "From here, many buildings of Troy can be seen," he writes.

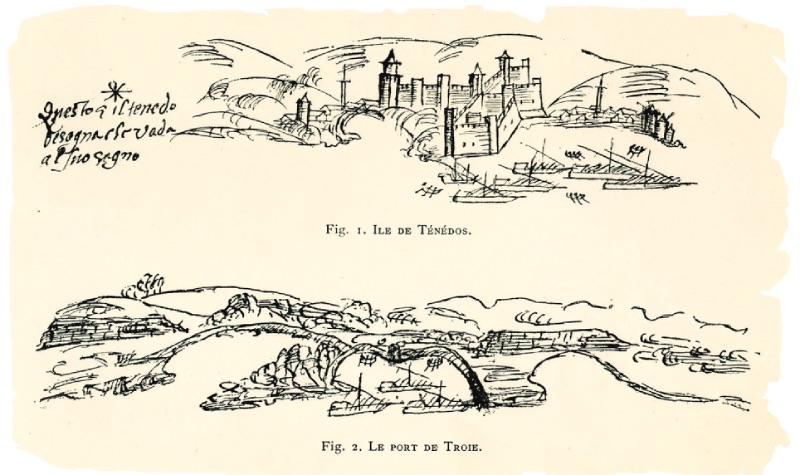

When entering the Dardanelles, he expresses, "Here was the entrance and harbor of Troy." As we wrote earlier, it is the historian from Imbros (Gökçeada), Kritovoulos, who writes that Sultan Mehmed the Conqueror visited Troy. However, from Kritovoulos's accounts, the first places that come to mind as the site visited by Mehmed the Conqueror are Alexandria Troas or the city of Sigeion at the entrance of the strait. The burial mounds (tumuli) seen by Mehmed the Conqueror must be the tumuli in the lower Karamenderes plain. In Piri Reis's Kitab-ı Bahriye, completed in 1521, the following is written:

"First, those who leave the caliphate center of Istanbul for the Mediterranean should know that there is no island closer to the Sultaniye and Kilitbahir fortresses in the Dardanelles than this island. This story is told about the island: While there was a fortress known as Old Istanbul on the Anatolian coast opposite Bozcaada, famous as Troy among the infidels, which was once prosperous but now in ruins, there was no fortress on Bozcaada. It has a harbor suitable for ships to dock."

Alexandria Troas, which can be observed quite well even from the sea, is regularly accepted and described as Troy for the next 150 years: The first detailed description of this place is made by the French traveler Belon in 1547, and it greatly influences subsequent travelers:

"The people living around Troy are partly Greeks, Turks, and Arabs. All the people living in this region call this area Troas. It is seen that the praises made in the poems of ancient poets about the beauty and grandeur of the city are not unfounded. The defensive walls that can still be seen today are so beautiful that words are insufficient to describe them. The walls surrounding the settlement prove how large the city was. Do not believe those who say that the ruins have been completely destroyed and disappeared."

Now, guides are available at the site of the ruins (Alexandria Troas), showing where Priamos's magnificent palace was and where Trojan women washed their clothes, establishing a one-to-one identification between the Troy legend and the ruins. From the 16th century onwards, travelers even began to take ancient artifacts from here as souvenirs and bring them to their countries.

Della Valle, who came from a Roman aristocratic family, anchored off Tenedos while waiting for a suitable wind to cross the Dardanelles during his journey to the holy lands in 1614. When he was told that the ruins opposite were the famous city of Troy, he became very excited and immediately visited. Drinking water from an old well in Troy made him very happy. Della Valle expresses his feelings as follows:

"I couldn't help but order a yacht to see the stone ruins of the famous city of Troy, which Vergilus referred to as gentis cunabula nostra, which inspired me, as I came so close... After reaching the harbor, I was filled with intense love and pride for the memory of my ancestors."

"In the area between Cape Sigaeo and the river Xanto, also known as Skamender (Karamenderes River), many ancient walls, columns, and other broken pieces can be seen... All these indicate that the ancient city of Troy was here."

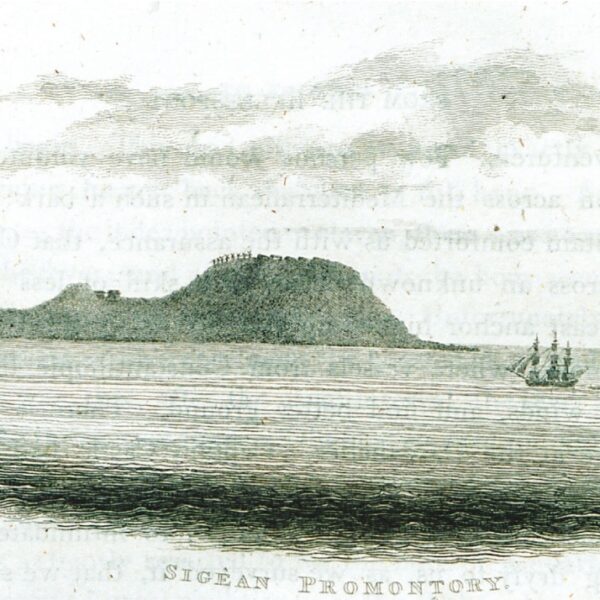

The localization of Troy is gradually changing with such descriptions. Yenişehir (Siegion) is replacing Alexandria Troas.

In 1675, Frenchman Jacob Spon writes: "The village that the Greeks still call Troja..."

After this, due to its strategic location, many travelers in the 16th-17th centuries believed that Troy was this ancient settlement and its surroundings at the entrance of the strait. However, the most important change in the efforts to search for Troy was made by organ maker Thomas Dallam in 1599. Dallam, who undertook the construction of the magnificent 5-meter-long organ that Queen Elizabeth I had made to present to Sultan Murad III, set out in 1599 to bring the organ to Ottoman lands and present it to the sultan, and his journey took months. During this journey, Dallam, who passed through the Dardanelles, visited the Greek village of Yenişehir on the Anatolian side right at the entrance of the strait. Dallam, who bought bread and chicken from the villagers he visited, described the impressive village at the entrance of the strait as a small and poor Greek settlement. However, Dallam first passed through what he and those around him believed to be Old Istanbul, and then:

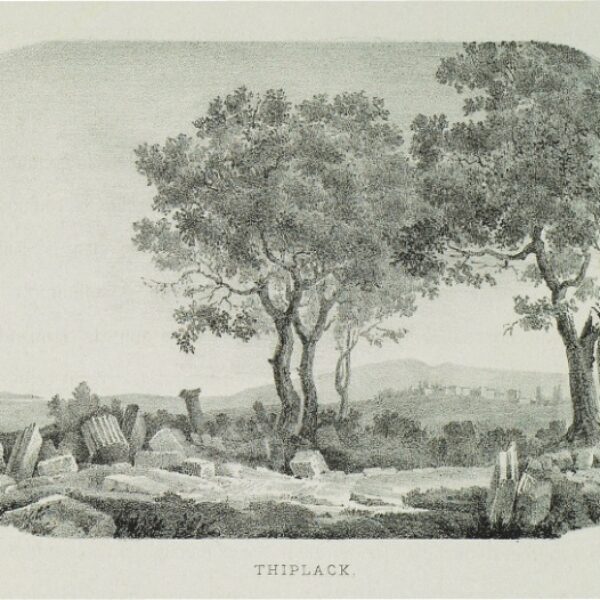

"Two hours after this galley, the wind began to slow down and brought us to the right, to a cape that some people call Yenişehir. I went ashore with some sailors. We came across a scattered Greek village. We bought some bread and chicken from the village. At the same time, we encountered a large ruin made up of the walls and houses of Troy. With the hammer in my hand, I broke off a piece of marble from a white marble column and took that piece all the way to London."

Yes, with these descriptions, Dallam, who was not a researcher, became the first traveler to visit two different Troys together. From the travelers' accounts, it is understood that the Greeks in that region did not know exactly where Troy was, at least since Seawulf's visit in 1103, they accepted all the ruins around Alexandria Troas and the Dardanelles as Troy.

After Dallam, the most important step in this regard was taken by the Englishman George Sandys, who set out to explore the world and experience adventures. In 1610, Sandys first visited Alexandria Troas and began to criticize the statements of P. Belon, which had been accepted until then:

"A mistake has been made regarding the location of ancient Troy. Because from the ruins he described and still visible..., in this area descending from a slope to the harbor, it is unlikely that many battles, long-lasting attacks, took place between the sea and the city."

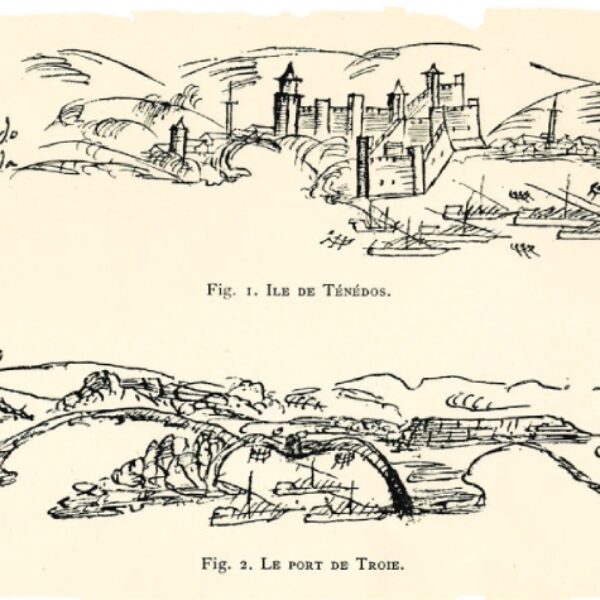

French naturalist Pierre Belon came to Alexandria Troas in 1547 and accepted without any doubt that this was the ancient city of Troy. This can be seen in the exaggerated map he published.

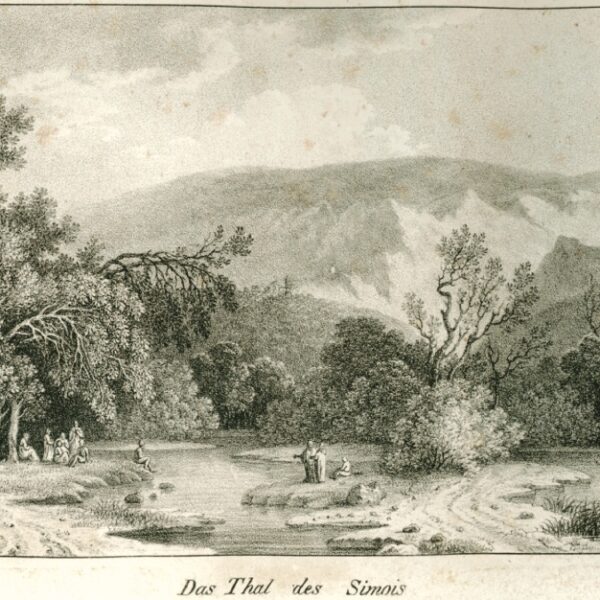

"This is the place where Ilion once stood, where two valleys close to each other form a large area. From these valleys flow the rivers Simois and the divine Skamander." Sandys cannot visit the interior of Troas but draws a sketch map showing Troy at the source of Ida.

Englishman George Wheler, from a noble family, visits Troas in 1675 with French physicist Jacop Spon. Especially Wheler's perspective on Troas is even more critical than Sandys'. Their archaeological observations with a critical perspective lead to the emergence of some doubts:

"A place with two or three tombs whose designs indicate a significant change from Rome to Arles. Their resemblance to others prevents me from having this view and believing that these tombs are the remains of ancient Troy. The most striking thing is the three arches and the surface of a wall, which seem to have remained from a very large structure, suggesting from afar that this structure was the largest palace in the city. But I don't think this structure was the palace of King Priamos in a city full of people living in prosperity, because I don't think these ruins are older than the early Roman Empire period."

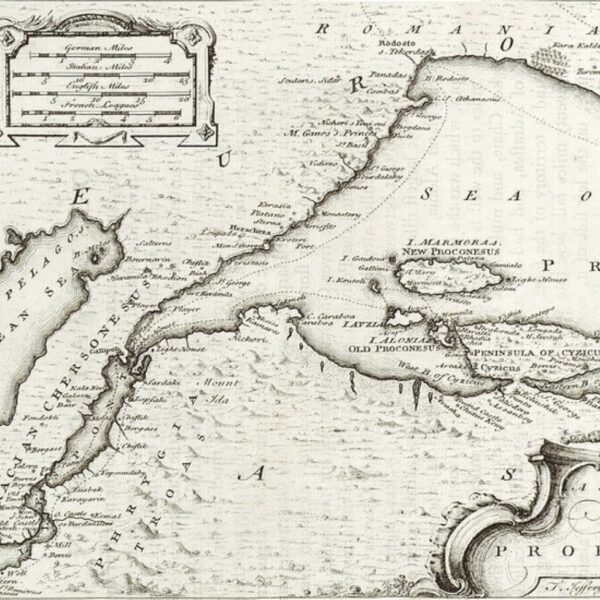

With these findings, a new period began in the localization of Troy/Ilion. The maps from this period also indicate the difference between Alexandria Troas and Troy/Ilion. Troy is increasingly shown in the mountainous interior rather than on the coast. In most of the descriptions made until the 18th century, it is accepted that the ruins of Troy were spread over a large area, and two places are mentioned as Troy: Alexandria Troas opposite Bozcaada (Tenedos) or Yenişehir at the entrance of the strait.

However, this view that lasted for centuries began to change in the 18th century.

So why did this change occur in the 18th century and not earlier or later?

Towards the middle of the 18th century, a new idea emerged that would further develop the perspectives until then. The discovery of the ancient cities of Herculaneum in 1738 and Pompeii in 1748 and the increased interest in archaeological excavations led to the emergence of this idea. Johann Joachim von Winckelmann, considered the father of classical archaeology who planned to excavate the ancient city of Olympia, wrote in 1767:

"I am very sure that the benefit here will be much greater than anyone can imagine, and with a detailed investigation of these lands, a great light will be born in art."

In addition, a fascination and effort began to be directed towards the architectural remains in Athens, while English aristocrats James Stuart and Nicholas Revett, meeting in Rome, established the Society of Dilettanti, a club where those interested in ancient sciences gathered.

Before addressing the significant effects of this club on Troy research, let's mention another development in the 18th century that also directed Troy and Troas research.

The interest and fascination with Homer and the Iliad among European intellectuals, especially at the beginning of the 18th century, were also reflected in the translations of the Iliad. The first French translation, published in an understandable style and with explanatory footnotes, was made by Anne Dacier in 1711. This translation also influenced the English translation made by Alexander Pope in 1715, which caused quite a stir at the time. These increasingly frequent translations of the Iliad fueled the desires of travelers and researchers who wanted to find Troy. Additionally, the map published by Pope along with his translation greatly influenced later researchers regarding the Iliad and Troas topography. Although the published map was criticized as a fictional product, for the first time, the most important details described by Homer, such as the harbor where the Achaeans docked their ships, the two rivers, the plain where the war took place, the city established at the sources of the Skamander river, and its entrance, Mount Ida, were brought together. Pope's annotated translation and this published map also served as a source for the Pınarbaşı Theory proposed by Lechevalier in 1785, which claimed that Troy was near Ballı Dağ, close to Pınarbaşı Village, and was partially accepted for a century.

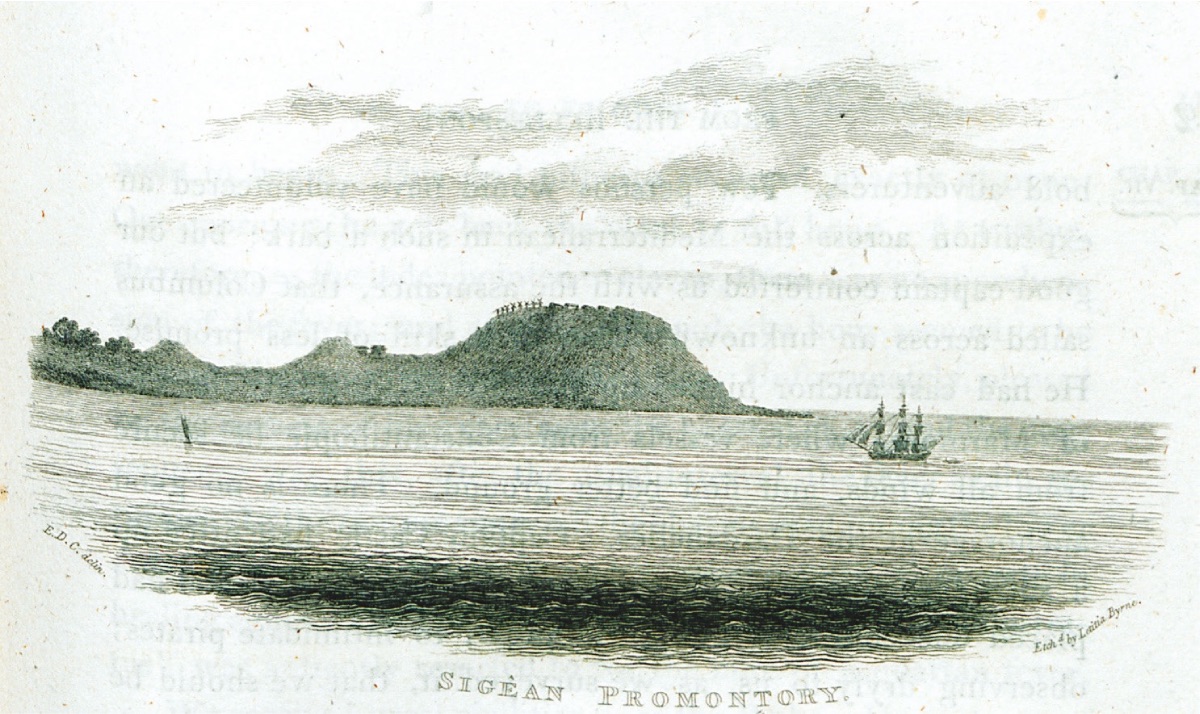

Lady Montagu, who lived in Istanbul with her husband, the British ambassador, between 1716 and 1718 and became famous for her letters, watched the plain of Troy from the hill of Yenişehir in 1718 and felt the following:

"I saw the hill where poor old Hecuba was buried at Janizary (Yenişehir), about a league away from the famous Sigeum cape where we anchored. Out of curiosity and excitement, I struggled to climb the hill to see the place where Achilles was buried and where Alexander undoubtedly paid great respect by circling the tomb in his honor. There, I saw the ruins of a great city, and Mr. Wortley could barely read the Sigean Polin inscription on the stone we found. We ordered the stone to be taken to the ship... What remains of Troy is only the earth. Nevertheless, looking at the valley and imagining the famous duel between Menelaos and Paris and the magnificent city gives me great pleasure. As I look at these famous lands and rivers, I admire the accurate nature descriptions in the Homer I hold in my hand."

The translation Lady Montagu held was Pope's. With that translation, her dreams about Troy and the Trojan War gained a little more vitality.

Pope's response to the letter written by Lady Montagu is as follows:

"I will not create a small problem, but you can provide illuminating information for many parts of Homer because you are under the same sun that inspired the father of poets. You are now breathing the same air that inspired him; you can feel his thoughts that excite you in the place where the story and events he described took place, touch the broken columns of hero tombs, and read the epic of Troy's fall in the shadow of Troy's ruins."

With Pope's dreams, the reality shattered in many ways by the ruins believed to be Troy began to take on a romantic essence.

With the acceptance that the sought-after Troy was not the magnificent Alexandria Troas, the archaeological find gap needed by 18th-century researchers for Troy and ancient fascination became a major problem, and efforts to search for Troy shifted from the Troas coast to the interior.

The first serious topographic research in the Troas region was initiated by the English traveler and researcher Richard Pococke, who came to Yenişehir in 1740 to search for Troy. Especially since the 17th century, the greatest fear of travelers has been pirates both at sea and on land. Pococke also hires two soldiers to protect and guide him:

"I hired two Janissaries to take me to Troy and its ruins the next day. The roads here are very dangerous."

Pococke arrives at a place called Buiek, somewhere in the middle of the road to Alexandria Troas in the southeast direction. Some researchers suggest that this could be the cemetery of Bozköy. Pococke's impressions are as follows:

"We came to a place with large ruins, broken columns, and marble blocks. I think Ilium was here. Just below here, the Skamander and Simois rivers merged, and the ancient Troy should have been near Ilium, on the height opposite the confluence of the two rivers."

Finally, from a high place, Pococke gives up his efforts to search for Troy at the confluence of the Karamenderes (Skamander) and another river, which he considers to be Simois:

"And I ended my efforts to find the remains of ancient Troy, which is believed to be above."

Pococke's extinguished hope does not negatively affect the desires of Robert Wood and his friends from the Society of Dilettanti to find the ruins of Troy.

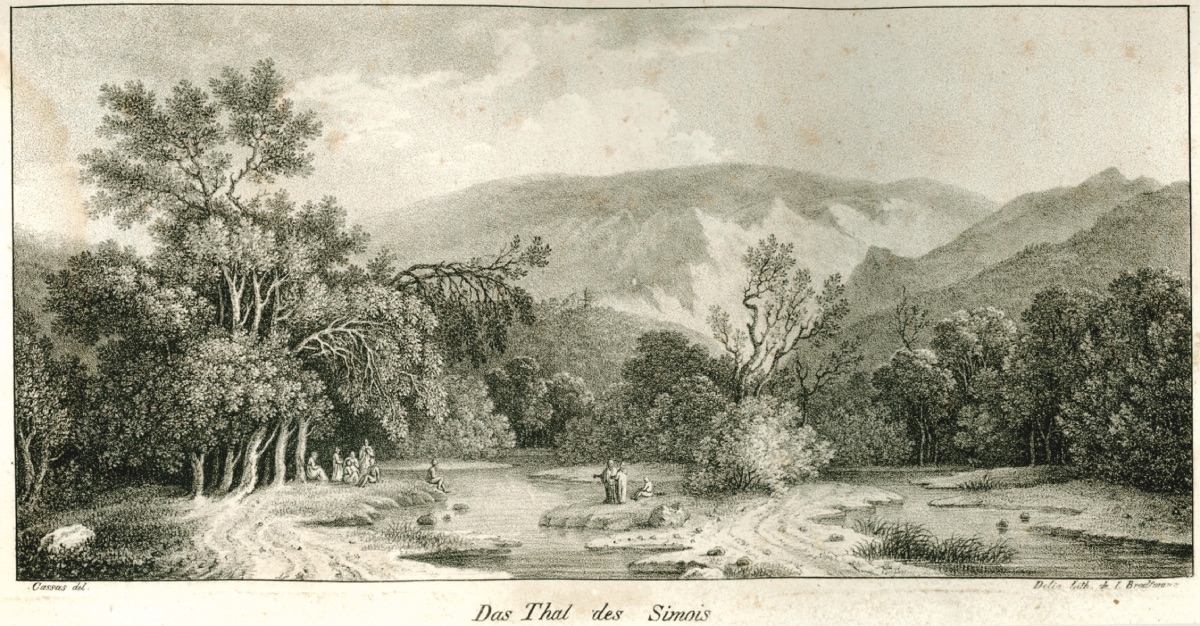

In light of this information, the project of Richard Chandler, also from the Society of Dilettanti, to research Troas along the Skamander and Simois rivers in 1764 is interrupted due to the danger of bandits:

"We thought of staying in Gavurköy for a couple of days. After resting, we would explore the plain in detail, follow Simois and Skamander to their sources, and head into the interior of Mount Ida. We were gripped by the fear of those wandering aimlessly in that area. Our guide wanted to go to his brother and family without interruption, and the increasing unrest of the Janissaries with us led us to choose the most sensible path."

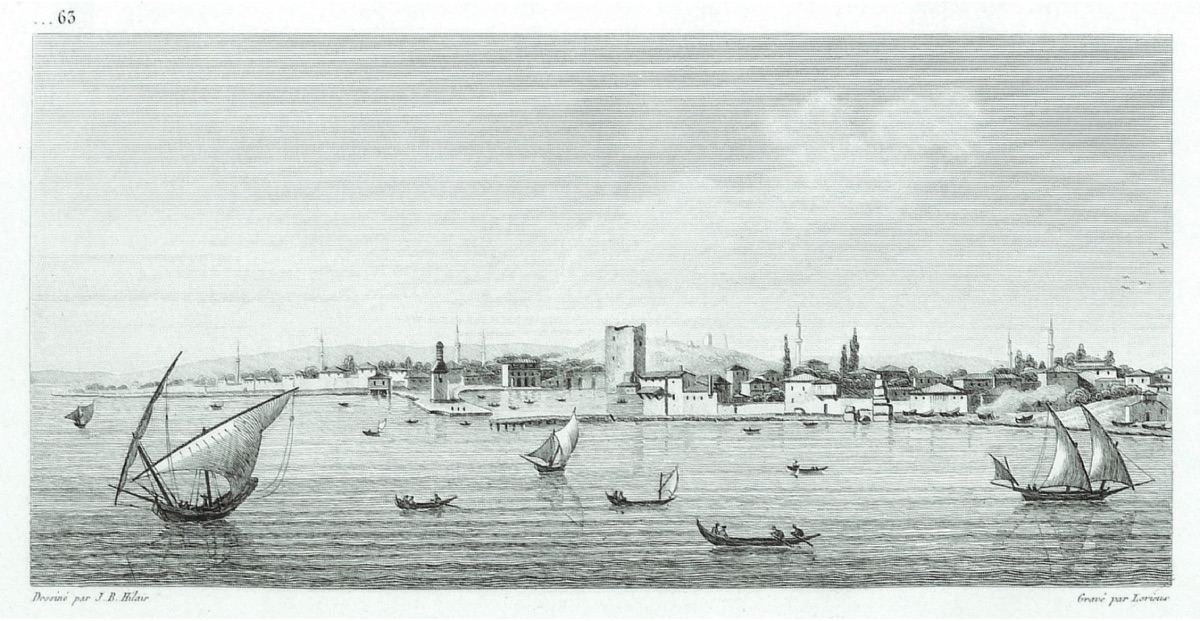

Chandler's travel notes from 1764 provide detailed information about the society and people in the Çanakkale region at that time. Chandler is the first to provide estimated information about the population of settlements and includes detailed descriptions of the interiors and exteriors of the houses people lived in. Despite the danger of bandits throughout the Çanakkale region at that time, Chandler continued his travels to understand the region in the best possible way. In this context, the traveler who also visited Bozcaada states that 600 Turks and 300 Greeks lived in peace on the island. Chandler's observations about the island continue as follows:

"In an area close to the center of the island, various groups come together to play music and dance, while women sit on the roof and watch the entertainment."

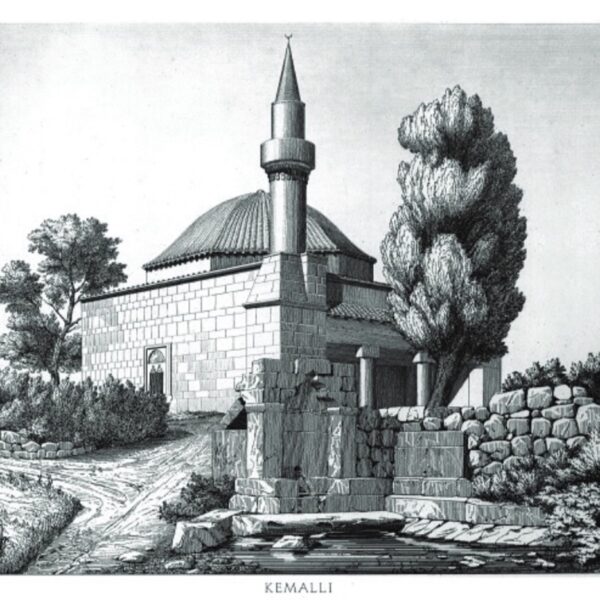

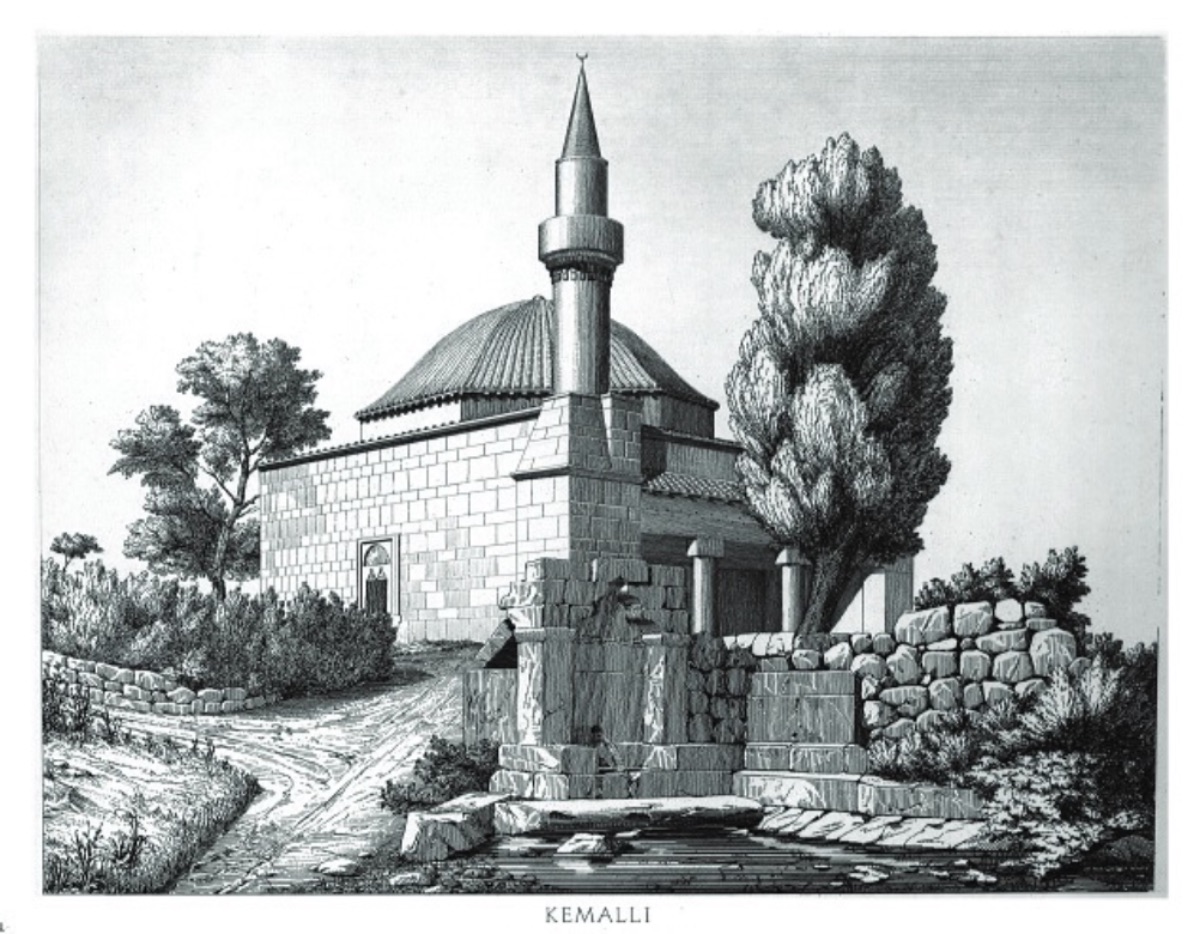

After the island, Chandler also visits the villages on the opposite shore. What he writes about Kemallı village is quite interesting:

"While the men were working in the fields, the adobe houses were filled with women."

The tradition of proving the Iliad Epic and the ancient city of Troy with authentic finds in ancient sources also began to put pressure on researchers interested in this subject. The German translation of Thomas Blackwell's "Enquiry into the life and writing of Homer" (1735) by Johann Heinrich Voss in 1776 greatly strengthened the view that the Iliad epic was based on geographical and historical realities. However, on the other hand, there were those who approached Homer and the Iliad from a critical perspective. For example, the famous German thinker Johan Gottfried Herder wrote the following on this subject:

"When I read old Homer, I am not at all interested in how Troy or the Trojan plain is now. I do not think of this Troy and plain as he described them in his epic poems (otherwise, it would be a bad epic poem)."

Such and similar comments that viewed the historical reality of the Iliad epic with skepticism were also increasing. Jacob Bryant, who published Wood's book, expressed his skepticism in a letter he wrote in 1755 as follows:

"I view the subject of the Trojan War with great skepticism. I am sure that Homer's city of Troy never existed... The passion for finding Troy, as Wood did, is a thing of the past. The world was waiting for this. As Pope said, everyone wanted to read the Troy epic with pleasure in the shadow of the ruins of Troy."

Yes, in the last quarter of the 18th century, the Troy front was divided into two: those who believed in the existence of the ruins of Troy and those who claimed that what Homer described was not real.

But still, the visits of European travelers to the Dardanelles and nearby places continued with great intensity.

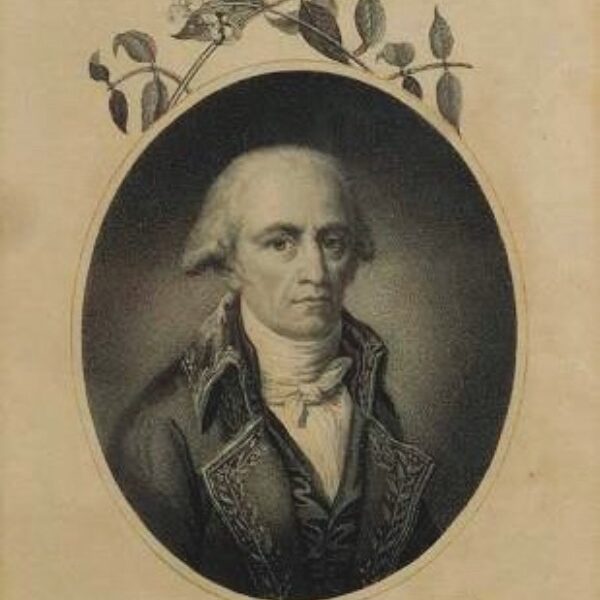

In this critical period, the stage is taken by the French Marie - Gabriel - Auguste - Florent Choiseul-Gouffier, an aristocrat with a very good education in painting, who shared his admiration for Homer with Wood. Choiseul-Gouffier traveled in the Mediterranean in 1776 to search for "Homer and Herodotus's Greek Homeland." His aim was to prepare an encyclopedia presenting the life of the Greeks living within the Turkish sovereignty and tradition and the findings of the ancient Greek homeland. In 1782, the first volume of his magnificent book "Voyage Pittoresque de la Grece," which included many wonderful engravings, especially about the islands, was published.

Choiseul-Gouffier became the ambassador of France to the Ottoman court in 1789, but the revolution that took place in France in the same year forced him to live in exile for four years for political reasons.

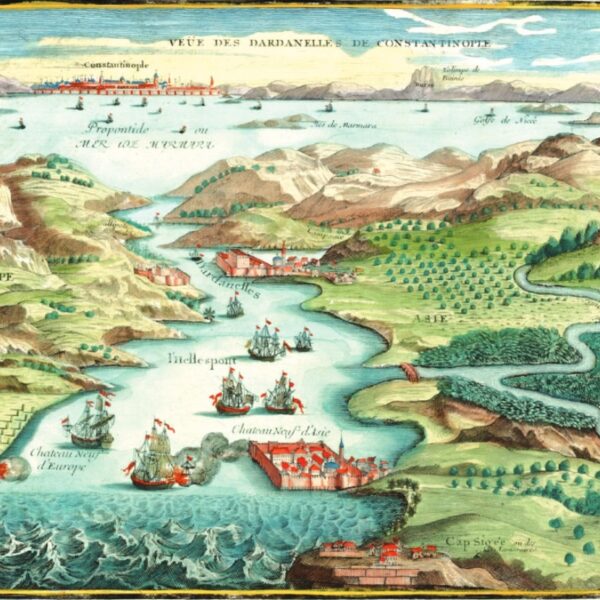

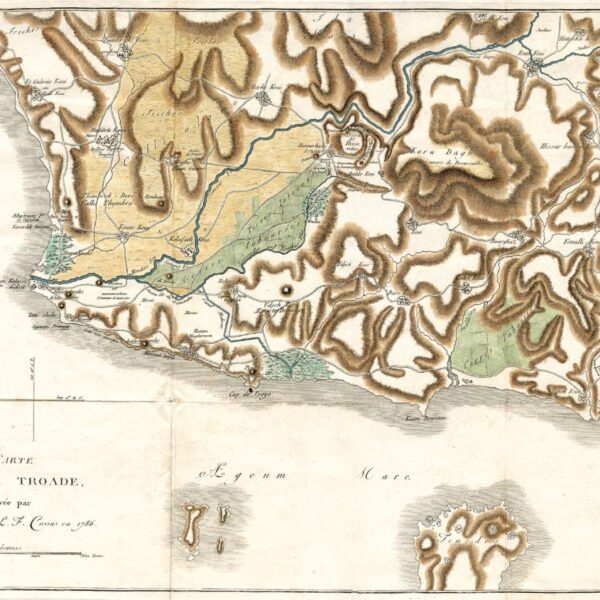

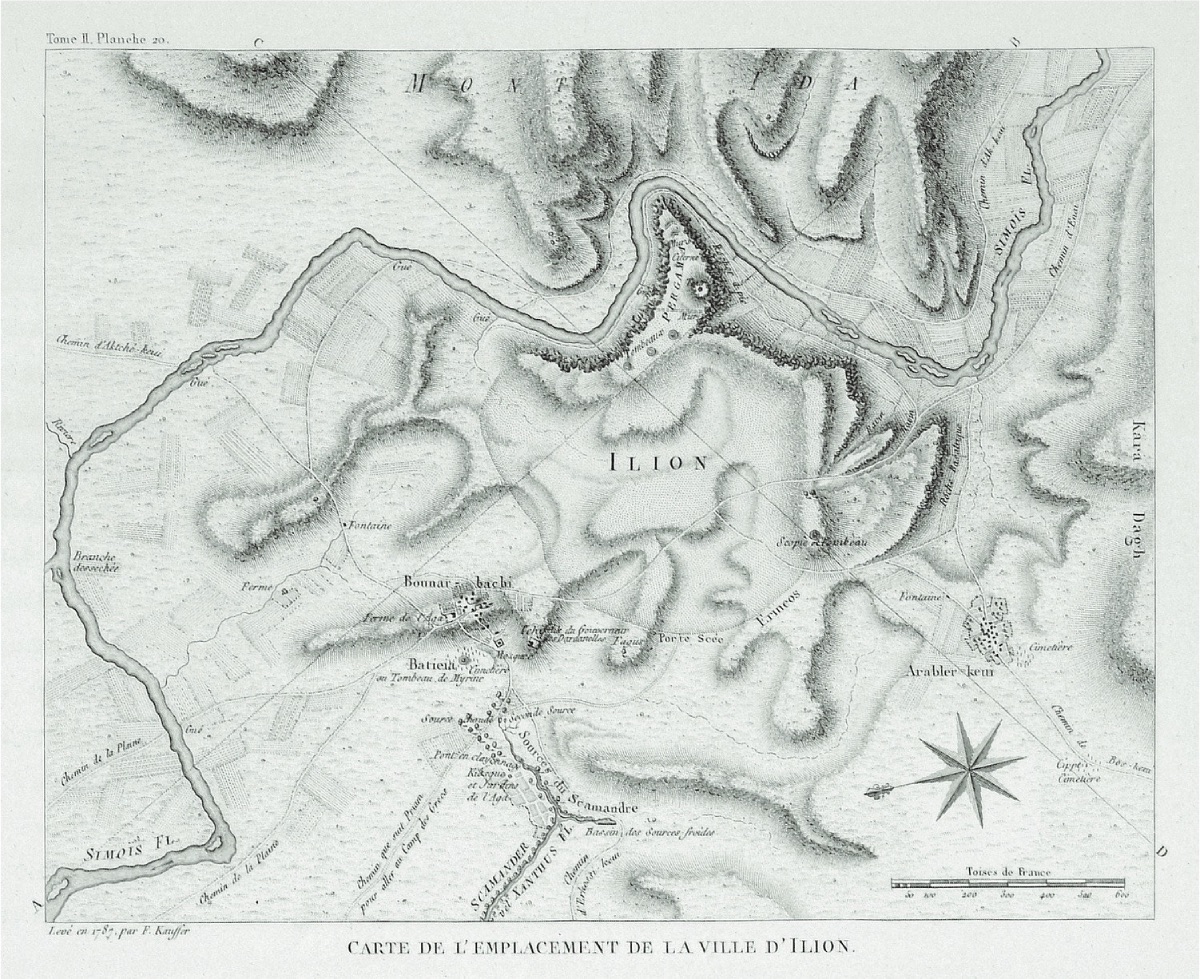

During these years of exile, he worked intensively on the Troas region, which he had previously visited. Choiseul-Gouffier also assigned Jean-Baptiste Lechevalier to map the Troas region. Lechevalier proposed the Pınarbaşı (Bunarbaschi) Theory, which was heatedly debated for a century.

Lechevalier's discovery of Pınarbaşı near Troy in 1785 and 1786 should be read more as a discovery that emerged as a result of the pressure and need among intellectuals and travelers after the disappearance of Alexandria Troas as Troy, rather than a discovery by a traveler passing through the Troas region.

LeChevalier's discoveries were followed with great interest by European researchers and travelers in Istanbul at that time. The new theory he proposed was the real topographical adaptation of the map prepared by Pope based on Homer. Ballı Dağ, the first major elevation about 8 km southeast of Hisarlık Hill, was the famous fortress in the epic. The first elevation right behind Pınarbaşı Village was the calm entrance of the city frequently mentioned in the Iliad. The sources of Pınarbaşı Stream, with nearly forty springs just below the village, were the two springs of the Skamander river mentioned in the Iliad, one cold and one hot:

"Achilles flies towards Hector just like that,

Hector flees in fear, trembling,

They run by the walls of Troy with all their might.

They pass the lookout place, the fig tree beaten by winds,

They move away from the walls, enter the great road,

They reach the two springs flowing beautifully,

The two springs of the swirling Skamandros gush there,

From one flows warm water, smoke rises above it,

Just like smoke from a fire,

From the other flows ice-cold water even in midsummer,

Cold as snow, hail, frozen water.

There are baths near these springs,

Wide, beautiful, stone baths,

Where the wives and beautiful daughters of the Trojans

Once washed their bright robes

In these baths during peacetime, before the sons of Achaea came

(Iliad XXII, 143-157, Turkish translation by A. Erhat, A.Kadir)

Lechevalier describes all this as follows:

"The heroes who died under the walls of Troy possessed divine honor. The sweet scents of incense burned from the tomb of Achilles rose, the entire Troy Plain was a great temple, and all the nations passing through the strait accepted offering sacrifices here as a religious duty. Here I see the great Homer setting foot on these famous shores. Sacrificial ceremonies are held in the shadow of Achilles. I see him walking in the harbor between Skamander and Simios. His eyes look at the objects around him as if enchanted (Homer's eyes only did not see in his old age). He imagines thousands of scenes, feels them in the depths of his heart, and with the enthusiasm of his creative power, he makes plans for the Iliad."

The topographical system proposed by Lechevalier was debated with great fervor without interruption. For many of his critics, the distance between the city and the harbor where the ships docked was too great, and it was impossible for Hector and Achilles to run around Ballı Dağ. The possibility of the very small Pınarbaşı Stream being the main water source feeding the plain was very weak compared to the Menderes Stream. As a result, the temperature of the water sources measured by all visitors was the same. Some critics, without delving into these details, accused Lechevalier and those who followed him of boundless imagination. Among them, the most famous and tireless was the English historian Jacob Bryant. Bryant had already addressed the Homeric tradition as originating from Egypt in his book on mythology published in 1774 and accepted it. His reaction to Lechevalier's new thesis was as follows:

"The Trojan War and the expeditions made by the Greeks, according to Homer's accounts, never happened, and there was never such a city in Phrygia. However, the personality of the poet and the beauty of his poems are still unparalleled. Their magnificence will never be harmed."

Yes, even if the existence of Troy was not accepted, the greatness of Homer and his epics continued to enchant everyone.

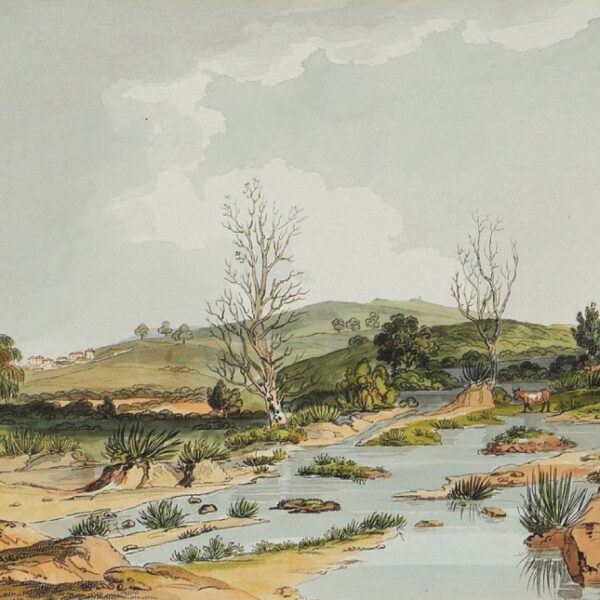

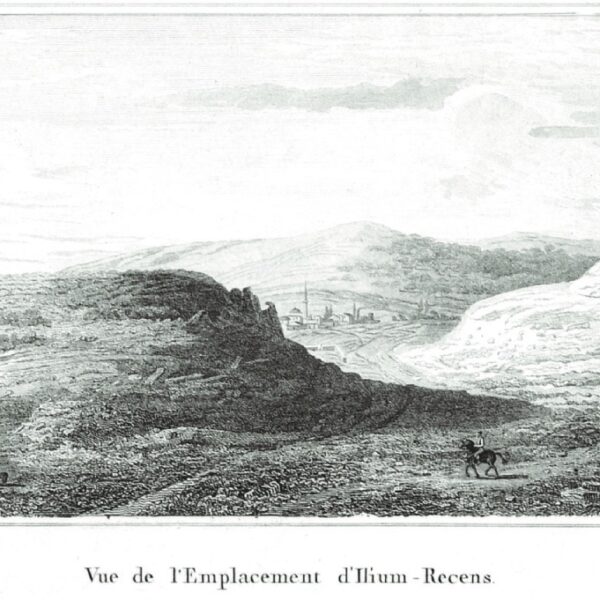

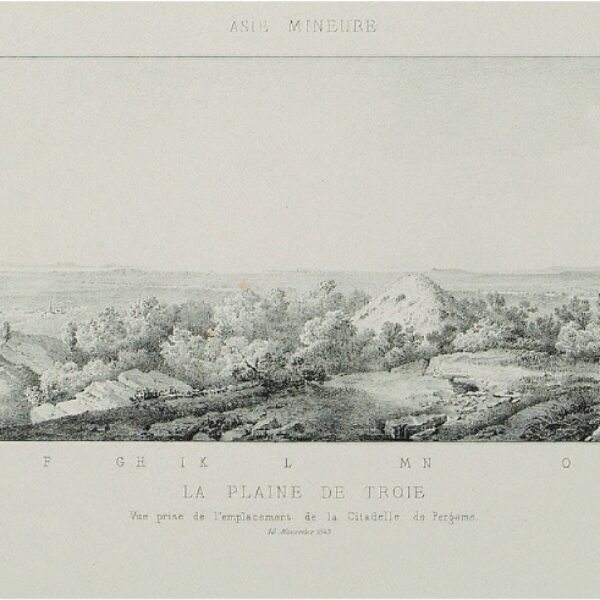

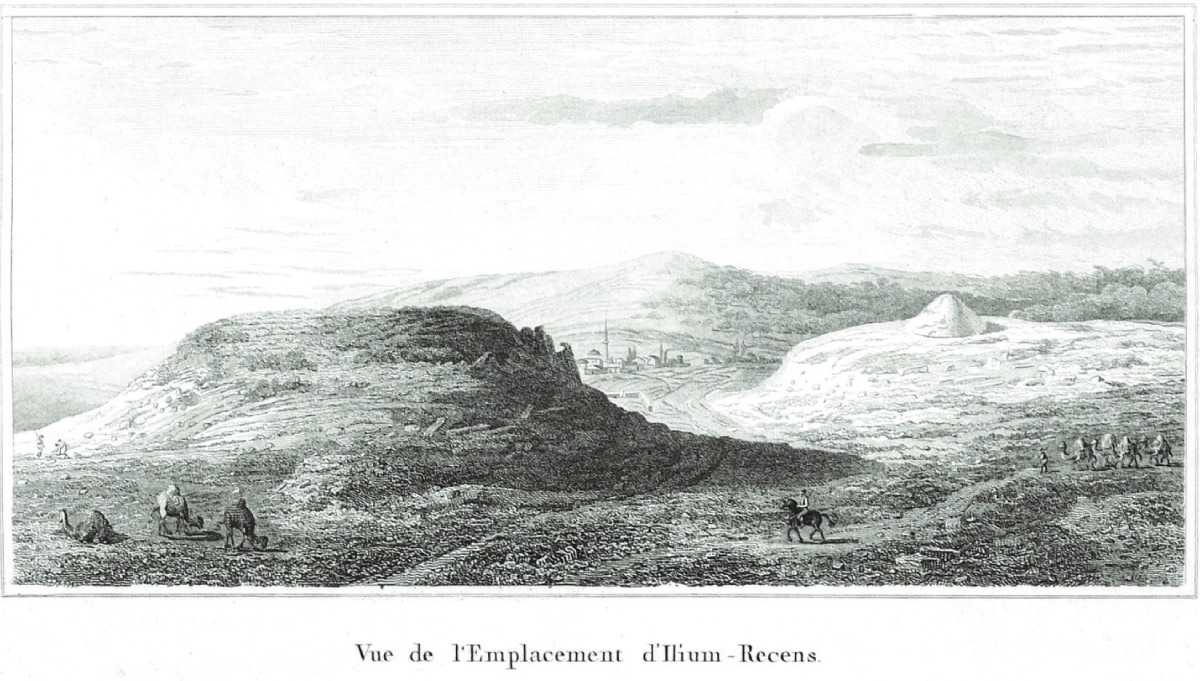

Meanwhile, the second volume of Choiseul-Gouffier's "Voyage Pittoresque," which dealt with the Troas region and included wonderful engravings from the region, was published in 1809. However, the second part of the second volume was published in 1822 after Choiseul-Gouffier's death. Among the engravings published in this edition, there is one with the caption "Vue de l'Emplacement d'Ilium Recens," which did not attract anyone's attention for many years. In this picture drawn from the Troy Plain, a not very high elevation with a few architectural pieces on and around it is seen. In the background, possibly Çıplak Village and the elevation on the right of the hill, Paşatepe tumulus (burial mound), attract attention. The hill, which did not mean much at that time, was Hisarlık Mound. After this engraving, it managed to hide itself from researchers for nearly a century.

The research towards Troy that began at the end of the 18th century continued at the same pace at the beginning of the 19th century. In 1801, young English researcher William Gell reached Alexandria Troas by following the coast and then reached the region where Troy and Ballı Dağ were located by land. During this trip, he made many drawings of the region and published his observations in a book in 1804.

Again in 1801, Englishman Edward Daniel Clark, who conducted research around Troy, partially benefited from Gell's drawings. Clark went to the region to conduct research at the request of Lord Elgin, the British ambassador in Istanbul, made drawings of the region, and created maps. Although not in his initial publications, he published the third volume of his book, which included his observations of the region, in 1812. In this publication, the location of Hisarlık Hill was marked as Ilium Novum. Clark made this determination by consulting with William Gell and using the maps he made. Additionally, the coins he identified during his visit to Hisarlık Hill supported this assumption. Following this publication, Choiseul-Gouffier, who was in Paris at the time, sent an expert to the region to gather information about Hisarlık. The publication "Vue de l'Emplacement d'Ilium Recens" in Choiseul-Gouffier's 1822 edition emerged as a result of this research.

In addition to these technical trips to the region, the number of romantic travelers coming to see the region with Homer's Iliad in hand was not negligible.

In the spring of 1810, the famous poet Lord Byron traveled from Athens to İzmir and then to Istanbul. During this journey, he had to wait in the Sigeion bay at the entrance of the strait due to strong winds. Before exploring the surroundings, his close friend John Hobhouse read him the first book of the Iliad, but Byron was not at all interested in what ancient scholars said about the topography of the region. His passion was different. It was the legend of Hero and Leander, the unfortunate lovers living on the opposite shores of the strait, that was on his mind. He was filled with the desire to swim across the strait from Abydos to Sestos in memory of these lovers. On May 3, 1810, at 10:00 am, accompanied by British soldiers, he swam across the strait in 1 hour and 10 minutes. His experiences in the region are clearly seen in his poem "The Bride of Abydos":

"The wind blows wildly and Hellas is excited

Throws itself into the magnificent darkness of the sea;

And like crouching, night covers everything,

In vain, it is stained with blood

The lands where Priamos lies with honor.

And the glory of Troy remains as a grave,

A grave and a face of dreams

Consoles with eternal light

The blind old man at the tip of Skios rocks."

Lord Byron writes the following in his diary dated 11.01.1821 regarding the discussions about Troy and Homer:

"The subject of the 'authenticity of the Troy epic' concerns us. In 1810, I watched this plain for almost more than a month every day, and the only thing that diminished my enthusiasm was the disgraceful Bryant's denial of reality. I showed great respect for the reality of history and place. Otherwise, could they enlighten me?"

Another example of romantic travels is the journey made by the famous Austrian orientalist Joseph von Hammer-Purgstall, who served as the secretary of the Austrian ambassador in Istanbul, to the Troas region in March 1800. While watching the burial mounds on Ballı Dağ in Pınarbaşı, Hammer-Purgstall wrote the following:

"O high hill! Around which

Hector's body was dragged, in memory of heroes

Alexander circled three times with his bare feet

around you, you cruel relic of times, for three thousand

years you have looked at the ships going to distant Hellespont and black Pontus,

you will be spoken of for much longer: this is the tomb of a hero, they will say."

Believing that the natural environment described by Homer perfectly matched the natural environment he observed, Hammer-Purgstall only discussed some minor details in Lechevalier's theory.

Subsequent discussions developed within the framework of the archaeological reconstruction of hero epics in a historical sense.

English geographer James Rennel addressed the Lechevalier discussion in detail in his book published in 1814 but could not reach a definitive conclusion. He localized Troy to an indeterminate point in the plain. He based this localization on the following lines from the Iliad:

"Cloud-gathering Zeus first became the father

of Dardanos,

Dardanos founded Dardanie,

at that time sacred Ilion did not exist,

the great city of mortal men did not exist in the plain."

(Iliad XX 216-218)

Rennel also used the map drawn by German engineer Franz Kauffer, who worked in the field on behalf of Choiseul-Gouffier, among other maps. With Kauffer's map, Hisarlık had been known as a ruin since 1793. As previously mentioned, Clarke identified this ruin as Greco-Roman Neu-Ilion with the help of the numerous coins found there.

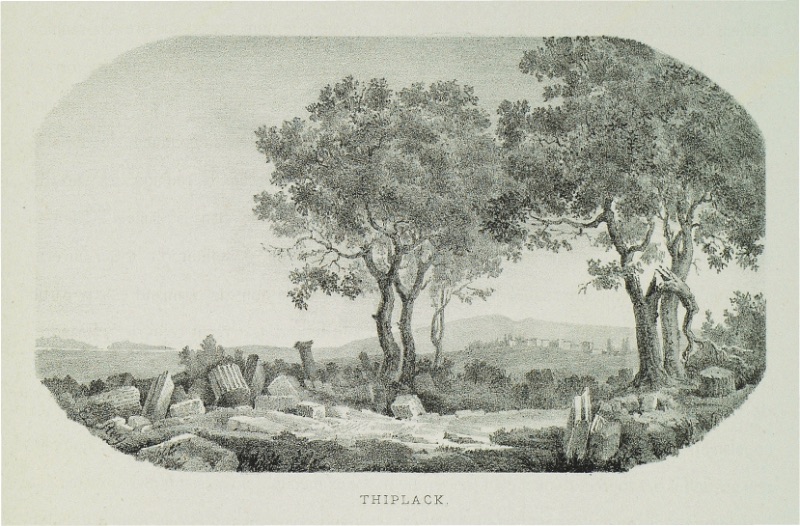

The next significant step was taken by English researcher and publisher Charles Maclaren, who worked at the desk without going into the field. In 1822, by thoroughly reviewing previous publications and considering the ancient tradition, Maclaren believed that Neu-Ilium should be identical to ancient Troy. Maclaren's visit to the Troas region in 1847 aimed to examine and evaluate the topographical features of the region on-site. He published his second book in 1865, which included his observations from these trips, further strengthening the Troy: Hisarlık thesis. However, not everyone was aware of the thesis proposed by Maclaren in 1822. Many researchers visited Pınarbaşı and Ballı Dağ, believing them to be ancient Troy. Some were disappointed by what they saw, while others continued to believe romantically.

For example, Englishman Charles Fellowes, who made significant discoveries in the Lykia region in 1838, 1842, and 1844, visited Pınarbaşı in 1838 and wrote the following:

"In this place accepted as ancient Troy and on the nearby hills, I did not find a single wall stone or any remains indicating any period."

A few days later, Fellowes noted that he saw Greco-Roman period remains belonging to Ilion near Çıplak village, just west of Hisarlık, without ever considering that it could be ancient Troy. At that time, the British consulate in Çanakkale was held by Mr. Launder, who joined the Calvert family through marriage. Although Fellowes wanted to stay at Launder's house, he could not because the house had recently been destroyed by fire. Contrary to Fellowes' disappointing trip, Helmuth von Moltke, who came to Istanbul between 1836-1839 to modernize the Ottoman army, examined the surroundings with a soldier's eye:

"From the Turkish fortress Kumkale, at the southern entrance of the Dardanelles, after walking for three hours along Simois, the valley at the foot of Pınarbaşı Village, where the Skamander's sources are said to be, merges with a cluster of hills. Again, from the same area, when you start to climb the gently sloping hill, you reach the hill that many travelers accept as Ilion. A thousand steps later, a gentle pass appears, and right next to it, a plateau with a castle on top, 500 meters long, appears before you. A small hill is shown as Hector's tomb... Researchers have different opinions about this place, but since we are not researchers, with a military instinct, we reach the place where an impregnable castle would be built, both then and now, and that place is Pınarbaşı."

This mistaken instinct supporting LeChevalier's theory by this master soldier is likely based on comparing it with the location of Mycenae, which he visited.

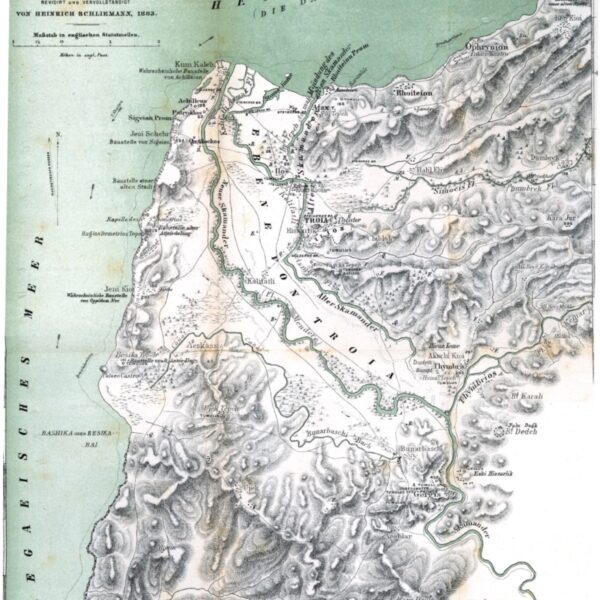

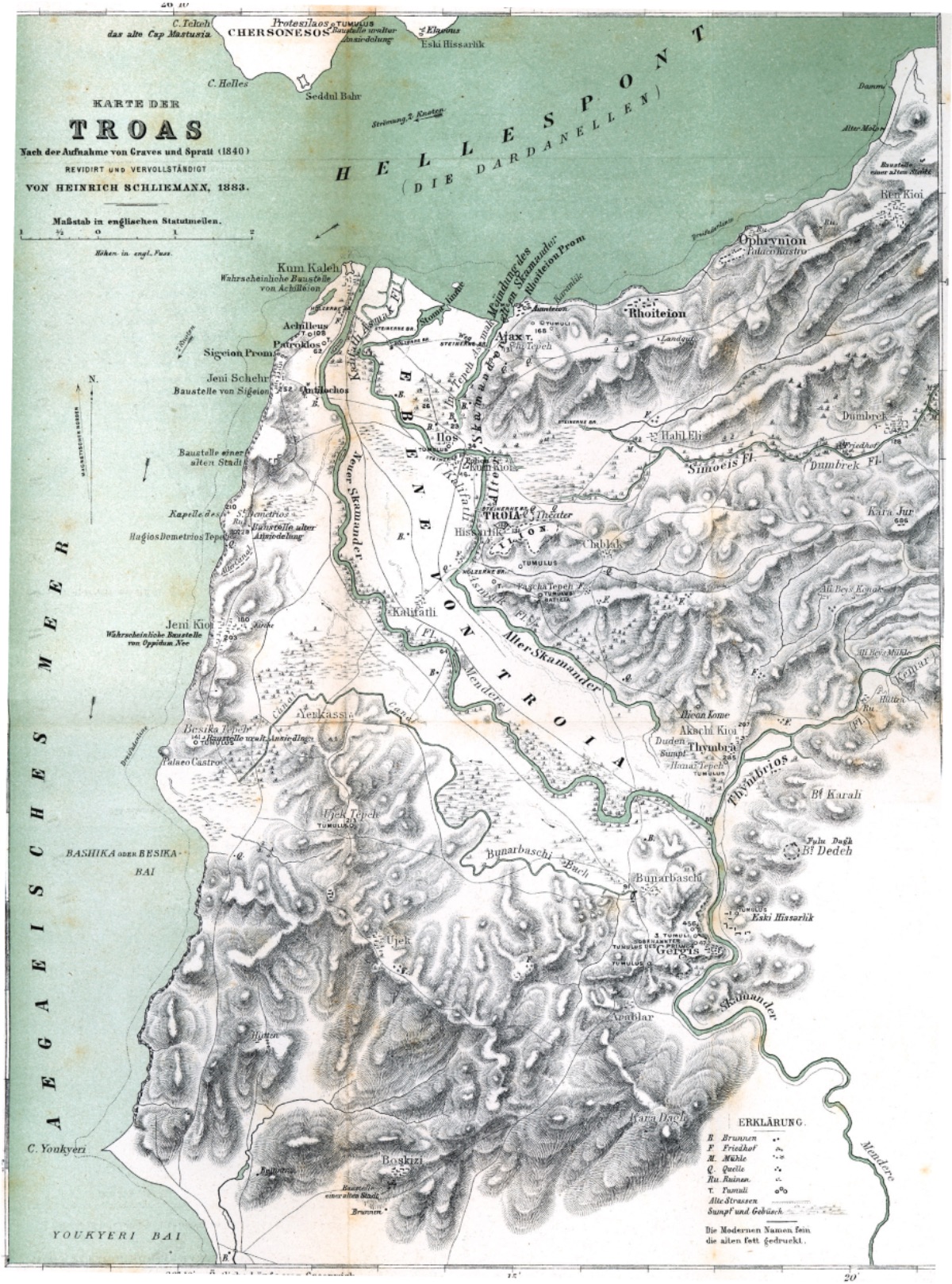

During the same years, another important work among those conducting research in the Troy region was the map prepared by Peter Wilhelm Forchhammer, a professor of history and philology at Kiel University (Northern Germany), in 1839 with T. A. B. Spratt. This map was the best topographic work prepared until that time.

Forchhammer set out in the fall of 1838 with a scholarship from the Prussian king to map the Troas region. He first went to Paris to purchase the necessary equipment for measurement work. Then he traveled to Malta via Rome and convinced Captain Grave, the admiral of the British Navy, to allow him to work together on the England Mediterranean Topographic Survey project. In these studies, Forchhammer undertook the task of collecting all data about the Troas coastal region. Additionally, a then-officer named Spratt was assigned to assist him with the measurements. Spratt later rose to the rank of general assistant.

Forchhammer first went to Greece and conducted topographic studies there. Then he set out with the British topographic survey ship and, after a stormy ten-day journey, arrived at Beşik Bay (the harbor 4 km southwest of Troy). The French and British naval fleets were anchored in the bay to protect the Ottoman Empire against the ships of the Ottoman's Egyptian governor Mehmet Ali Pasha, who had rebelled. The ships anchored here also served as a base for Troas region research.

On August 14, 1839, Forchhammer and Spratt began their fieldwork. During the month-long topographic studies, they stayed in tents in the field. Forchhammer returned to the ship due to illness. Spratt continued the work without interruption. As Forchhammer's illness worsened, he returned to Germany via Istanbul, Izmir, Rome, and Alexandria, despite wanting to excavate the İntepe tumulus. The work was first published in London in 1842. The revised and worked-on German edition could only be published in Frankfurt in 1850 after the Germany-Denmark War.

Although the work adhered to LeChevalier's Pınarbaşı/Troy theory, it presented an extraordinary detailed study that even today's researchers can still use. The map is filled with details such as village settlements (Greek/Turkish), ancient ruins (architectural/pottery), burial mounds with their heights, the localization of ancient settlements (Ophryneion/Rhoteion/Sigiei), all streams, sources, channels, dams, field boundaries, and what is planted. The location of Hisarlık Hill is marked as Ilium Novum (New Ilion).

Forhammer and Spratt's work particularly interested Mac Laren. As previously mentioned, Mac Laren addressed the Nuvum Ilium/Troy identity in his book published in 1822. After the Forhhammer/Spratt work, Mac Laren visited Troy in 1847 and worked a little more on his 1822 book, re-examining the Nuvum Ilium/Troy: Hisarlık theory in a more detailed and convincing way in his book published in 1863. This book drew the attention of Frank Calvert, the British consul in Çanakkale, who previously believed in LeChevalier's Pınarbaşı theory, to Hisarlık.

Before addressing Calvert's work at Hisarlık, let's talk a little about the Calvert family, whose graves are still in Çanakkale.

The Calvert family is originally from England but is scattered across the Mediterranean region, especially in Rhodes, Izmir, Thessaloniki, Alexandria, Istanbul, and Çanakkale, engaged in trade, diplomacy, and banking. The first member of the family to serve as the British consul in Çanakkale was Frederick Calvert. The second was James, and the next was Frank. Frederick Calvert came to the Troas region in 1834. At that time, Launder, previously mentioned, was serving as the British consul. Frederick Calvert was a sportsman who established very good friendships with the Turks, going hunting with the Agha of Bayramiç every autumn.

The Italian-style villa of the Calvert family on the Dardanelles was also a place where important people in the region gathered for 5 o'clock tea. The Calvert family also had two farmhouses, one in İntepe and the other where the old Akça Köy swamp was (Thymbra Farm/now the Agricultural Enterprises Farm). Like Frederick Calvert, Frank Calvert also bought land in the Troas region in 1857 to engage in farming. The purchased land included part of Hisarlık Hill.

Meanwhile, due to the ongoing Crimean War, active periods began in the Çanakkale region. The British government wanted to build hospitals for military purposes in Izmir and Abydos (Çanakkale). Engineer Mr. Brunton was assigned to this task from London. When he arrived in the region, he chose a place near Erenköy, about 8 km southeast of Troy, for the hospital construction. It is likely that he met Frederick Calvert due to his official duties. Brunton is mentioned in archaeological literature as the person who drew the map in Frank Calvert's article published in 1860 about the Erenköy region. As soon as peace negotiations related to the Crimean War began, Brunton was ordered to stop the hospital construction. Thus, the 150 people under his command suddenly became idle. This problem led to the first excavation at Troy. In 1855-1856, Brunton conducted excavations in several places in Troas. Among these places was Hisarlık Hill. The excavations at Ilium Novum, i.e., Hisarlık, covered the area where the bouleuterion (Roman period council building) was located. Bruton wrote the following about his work:

"I found the remains of a temple. It was made of the most beautiful white marble I have ever seen, and it was understood that one of the Corinthian temple columns had collapsed due to an earthquake. It weighed more than 3 tons. We had a hard time uncovering the piece we found. There was no road to transport it by car. Therefore, we had to push it down from the top of the hill where we found it, and it rolled down with great difficulty, and I had to leave it there with great sadness."

However, Bruton’s excavations were not the first in Troas. Danish P. Bröndsted, who visited Troas in 1810, wrote the following:

"Looking at these ruins, one immediately thinks of opening one of these tumuli and finding a bronze cremation vessel (of the burned heroes)."

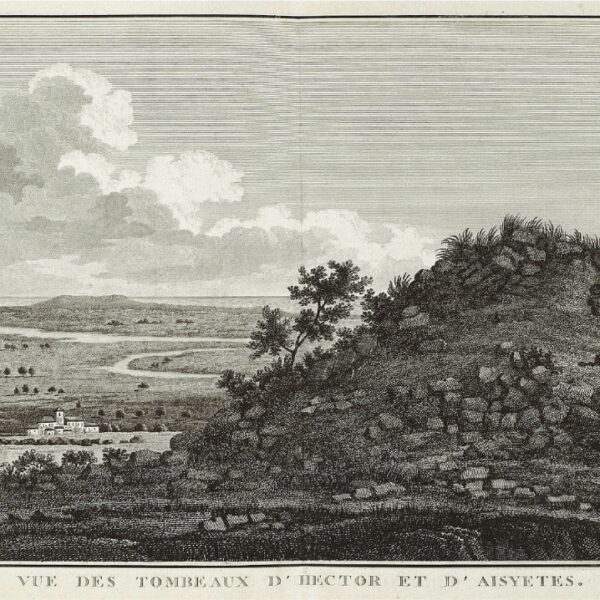

This digging thought led Choiseul-Gouffier to excavate the tumulus known as "Achilles' Tomb" just below Yenişehir Village in 1787. However, only Hellenistic period finds emerged. English researcher John B. S. Morrit also excavated the tumulus attributed to Hector in the Troy plain in 1795. The result was the same. However, during the same years, there were methodological changes in the archaeological interest in the region. As previously mentioned, Clarkes identified Hisarlık as Neu-Ilion based on the coins found there.

Bröndsted countered the then-valid Pınarbaşı-Troy thesis with the following arguments:

"Bonarbaschi (Pınarbaşı) is quite a large, open village, and around it, column and similar remains can be seen. There are traces of an ancient settlement, but there is no trace of a very ancient city here. For example, there is no trace comparable to the cyclopean walls known from Mycenae, Tiryns, and Ithaca."

As mentioned above, Forchhammer and Sprat produced the most detailed map of the region in 1839. This map later somewhat solidified Mac Laren's Hisarlık-Troy theory.

Between 1812 and 1816, William Turner, the second consul of England in Istanbul, wrote the following about Hisarlık:

"The hill, which we think is 'New Ilium,' is called Hisarlık (Issarlık) by the Turks. The ruins, if they can be called ruins, because they are gradually disappearing, consist of small stones. Among them are marble tile fragments. The stones are scattered on top of the hill, and one stone is not on top of another."

Charles Thomas Newton, the deputy British consul on the island of Lesbos, visited Troas in 1853, but before visiting, he met with Spratt in Malta and received information about the Troas region. After staying for a few days at the homes of Frank and James Calvert in İntepe (Renkoi), Newton went to Pınarbaşı to search for Troy. His impressions are as follows:

"To understand whether this hill was an acropolis, we first hoped to find traces of early pottery remains, which Mr. Burgon had recently noted in the Homeric settlements of Mycenae and Trynis. In the soil, I found no trace of such pottery or rock-cut foundation walls on the surface. Perhaps the remains were removed by terracing the hill by the late Greek city above...

From Kalafatlı, we proceeded towards Ilium Novum, which appeared very small from the surface. Due to the irregularity of the surface, I think the remains may be hidden underground."

In parallel with the archaeological research of that period, the arguments regarding the localization of Troy also began to change. In addition to Homer's descriptions, pottery and the surface of the mound began to come to the forefront in evaluations.

After Brunton's excavations at Hisarlık in 1855/56, Frank Calvert, who had conducted excavations in many places in the Troas region, excavated the prehistoric settlement of Hanay Tepe near Akça Köy, not far from Hisarlık, believing it to be the "common tomb of the Trojans."

In 1864, Austrian consul Johann Georg Hahn, stationed on the island of Syra, conducted excavations on Ballı Dağ in Pınarbaşı in 1864 with his friends Juluis Schmid and Ernst Ziller, with Frank Calvert as their guide.

Hahn wrote the following about the excavation results:

"There is not a single sign indicating the existence of a large city from Ballı Dağ's northern slope to the Pınarbaşı springs that would point to the Troy in the Iliad. Despite our persistent searches, we found nothing but the aforementioned burial mounds indicating an ancient human settlement. There was not a single piece of pottery or tile fragment that testified to an ancient settlement... Everywhere was an untouched natural surface."

Hahn published the city wall remains and other remains from the Hellenistic period he found on Ballı Dağ in a small booklet in 1865. Regarding this publication, Ernst Ziller, who worked with Hahn on Ballı Dağ, wrote the following interesting note in his diary:

"I obtained this brochure for Dr. Schliemann, who came to Athens and wanted to go to Troy for the first time."

Calvert, who conducted the excavation very meticulously, excavated the Greek-Roman layers at the site of the Athena Temple. Although he could not reach the Bronze Age remains beneath this layer, he realized that there were older layers below.

Frank Calvert wrote a letter to Carls Newton, the director of the British Museum in London, whom he met through a Troas visit, expressing his desire to conduct excavations at Hisarlık. In his letter, he also mentioned that he had discovered the Athena Temple thanks to the architectural artifacts and inscriptions from his excavations, that he had conducted soundings in the theater, and that a part of the mound had long belonged to him. However, Calvert's request was rejected due to doubts about his archaeological skills. Calvert did not have the financial means to finance the excavations himself. His brother Frederick Calvert had to leave the country due to some financial problems. Yes, Frank Calvert was waiting helplessly.

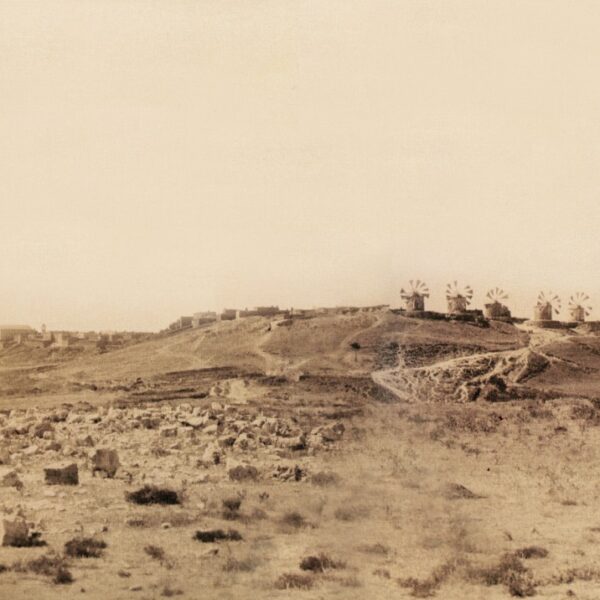

Finally, German Heinrich Schliemann set foot in Çanakkale at 6:30 on August 8.

It is likely that the brochure given to him by Ernst Ziller also influenced him, as he immediately went to Ballı Dağ in Pınarbaşı to search for Troy. He conducted trial excavations with a few workers at Ballı Dağ and Pınarbaşı springs. He did not find what he was looking for. Schliemann noted the following in his diary:

"I traveled from Piraeus to Çanakkale by ship. From there, I went to Pınarbaşı village in the south of the Troy plain. The Ballıdağ rocks rising behind it were recently considered to be the Ilion mentioned in Homer. The springs at the foot of the village were to be understood as the hot and cold springs mentioned in Homer. At the site of these two springs, I found exactly 34 springs; perhaps their number is forty, as the Turks call this place 'Kırkgöz.' Apart from this, the temperature of all the springs was 14 degrees.

The distance from Pınarbaşı to the Aegean is exactly 8 miles. However, the data in the Iliad seem to prove that the distance from Ilion to the Aegean was shorter and at most 3 miles. Similarly, if Troy were located at Pınarbaşı, Achilles could not have chased Hector around the walls of Troy in the plain. All this convinced me that Homer's city could not be here... I share the idea with my friend, America's Çanakkale consul F. Calvert, that this is 'Gergis.'"

It is clear that he wrote his diary after visiting Frank Calvert. This visit, which changed the fate of Schliemann and Troy, occurred by chance.

"Yesterday, I met the famous archaeologist Frank Calvert. Like me, he believes that Homer's Troy cannot be anywhere but Hisarlık. He told me that I must excavate there."

Later, Schliemann began to correspond intensively with Calvert. Calvert informed him about publications unknown to Schliemann, such as Mac Laren's, and sent him detailed information about Hisarlık and the Troy plain. For Calvert, Schliemann was a savior, a partner who could carry out the excavations he had wanted to do for years. For Schliemann, Calvert was a real guide who knew the region and was aware of the latest publications.

The friendship that began under these conditions experienced many ups and downs during the Troy excavations and turned into an "enmity."

On February 17, 1870, Schliemann wrote to Calvert, expressing his desire to start excavations at Hisarlık immediately and asking him to send a list of the necessary materials and publications for the excavation. Corresponding from Paris, he requested permission from the Greeks to excavate in Mycenae. At that time, unlike the Ottoman Empire, Greece had a law regarding antiquities. But when he arrived in Athens, he learned that his request had been denied. Due to problems with his wife Sophia, he saw the islands as an escape and visited them. In April, permission was granted for him to excavate in Mycenae. But before that, he embarked on another trip to see the Anatolian coast. His wife was not with him this time either. His trip ended in Çanakkale. On April 9, 1870, he began excavating at Hisarlık with four workers. He had not spoken to any official institutions or landowners. Ten days later, he was expelled.

Returning to Greece, Schliemann postponed his excavations in Mycenae for a while. The reason was that in mid-April, many tourists were attacked, robbed, and some were killed in Marathon. He did not want to start the excavation under these conditions. His sole aim was to start large-scale excavations at Hisarlık. However, obtaining an excavation permit for Schliemann would not be easy. In mid-January 1870, by order of the Minister of Education Saffet Pasha, the western part of Hisarlık was expropriated from two Turkish owners. Schliemann, who had previously conducted excavations at Hisarlık without any permission, was not wanted to be given permission. However, Schliemann, who was also an American citizen, managed to obtain permission by involving American ambassadors:

"I needed a firman from the Sublime Porte to conduct excavations in larger areas. However, in September 1871, with the benevolent help of my friends, the ambassador of the United States in Istanbul, Mr. Wyne Mac Veagh, and his late translator Mr. John P. Browon, I obtained my firman. Finally, on September 27, I set out for the Dardanelles, this time with my wife Sophie Schliemann... However, due to the constant difficulties posed by the Turkish authorities, we could not fully start the excavations until October 11. Since there was no place to stay, we had to set up camp in Çıplak, 2 km away from Hisarlık."

Schliemann soon began staying in the barracks he had built in Troy. The excavations were closely monitored by representatives sent by the Ottoman Empire.

Despite everything, Schliemann continued his excavations with great ambition and found the "Treasure of Priamos" in 1873 (sometime between February and June) and secretly smuggled it abroad. He became embroiled in a legal battle with the Ottoman Empire. He was fined. But thanks to money and important connections, he managed to return to Troy. He resumed excavations in Troy in October 1878. Meanwhile, he published his findings from Troy. He received both positive and negative reactions. He was especially accused of charlatanism by Ernst Bötticher. It was claimed that Troy was not a settlement but a necropolis with cremation burials. In November and December 1889, the first Hisarlık Conference was held with the participation of experts of that period (including Osman Hamdi Bey). Schliemann responded to the accusations on-site in Troy.

Despite his long-standing ear disease, Schliemann constantly traveled and worked like a madman. He died on December 26, 1890, at the age of 68 in Naples. He left behind a pile of problems and an equal number of books.

The excavations at Troy continued with interruptions until today.

Schliemann set out to provide historical and archaeological answers to the complex Troy problem that had persisted until his time. By pushing the boundaries of Dream and Reality, he provided answers to this problem. He made great mistakes in some, and he was right in others. But there is an undeniable fact that Troy, after Schliemann, gained a very different subject matter.

The legend of the city of Troy, oscillating between Dream and Reality, thus continues.