"Beyoğlu, April 13, 1836.

On the evening of April 2, I departed from Istanbul on an Austrian steamer and the next morning saw the high, beautiful mountains of Marmara Island. To the right appeared the mountains of Tekirdağ with its vineyards and villages. Soon, the European and Asian shores drew close to each other, and on the jagged, steep cliffs appeared Gelibolu, with its old fortress on the shore and countless windmills. This was the place where the Turks first crossed to the European side (1357). By noon, the white walls of Nağra Castle rose from the clear blue waters of the Hellespont. In terms of beauty, this strait is quite far from the Bosphorus. However, historical memories make it charming. From this strange-looking hill (perhaps a man-made hill), Xerxes watched his countless soldiers being taken to Greece. The piles of stones covering this low tongue were once Abydos, where Leander swam from Europe to Asia to see Hero. A shapeless single wall remnant still stands where the city once was. But it is difficult to say what these ruins once were. On the other hand, it is very likely that the people of that city, perhaps even the beautiful Hero, drank from the sweet water spring that still gushes from an underground cellar in the low isthmus surrounded by the sea.A strong current quickly took us to the narrowest part of the strait, "where the ancient darkened fortresses face each other." Behind the European shore rises a steep, white rock slope. In its side is a small cave said to be the tomb of Hecuba. The tongue on which the Kilidbahir fortress stands was called Kynossema, meaning the dog's tomb, by the ancients. It was believed that Hecuba, the wife of King Priam of Troy, was turned into a dog and buried here. In contrast, the Asian shore is low, and behind the fortress once established by the Genoese, there is a town surrounded by vineyards and gardens in the shade of enormous plane trees. The Turks call this town "Çanakkale" because of the many potters working there. The Boğaz Pasha resides in an unpretentious house there. I was tasked with delivering a letter from the serasker to him and conveying some things orally. He vacated a small, charming house on the shore for me. After examining the fortress and batteries, I drew a plan of the Çanakkale strait and its shores.

What I have to say about the task I was assigned, which is very interesting to me, is only general and mostly already known.

At the entrance of the Çanakkale strait, there are new fortresses built by the Turks in the example of the ancients. The one on the European side is called Seddülbahir "the fortress that closes the sea," and the one on the Asian side is called Kumkale. The opening at the mouth of the strait is almost one and a half geographical miles. These fortresses can be seen as outposts that will not only warn of approaching enemy fleets but also prevent them from anchoring in the inner parts of the strait. The main defense begins two miles further up and relies on the batteries placed in an area approximately one mile between Çanakkale and Nağra. Between Sultan-ı Hisar and Kilidbahir, meaning the sea lock, the strait narrows, and its opening decreases to 1986 feet. The cannonballs of these very solidly built fortresses or large batteries placed side by side reach from one shore to the other. Further up at Nağra, the width of the strait increases to 2833 steps.

For the defense of Çanakkale, there are 580 cannons. These range in caliber from 8 to 1600 Pfund (approximately half a kilo to 800 kilos). Some are five times the length of their caliber, while others are 32 times. Among them are Turkish, English, French, Austrian-made ones, and even some with the Kurfürst coat of arms. However, most of the cannons are of medium caliber suitable for the purpose and almost all are made of bronze. In Seddülbahir, there are a few strange large-caliber cannons made of wrought iron. Thick iron rods have been placed side by side lengthwise and wrapped with other rods, but they have not been very successful in this. A huge amount of money has been invested in these weapons.

The large embrasures that throw stone cannonballs made of granite or marble are quite strange. They stand on the ground without carriages under the vaulted door corridors in the fortress walls and on unconnected logs. Their sizes weigh about 300 quintals and are filled with 148 pfund of gunpowder. The diameter of their marble channels is 2 feet, 9 inches; one can crawl all the way to the gunpowder chamber. To prevent recoil, they have built walls of large stones behind the tails of these, but these walls are completely destroyed after just a few shots. However, the stone cannonballs skip over the water's surface and reach quite far inland on the opposite shore. Thus, if a cannonball hits the waterline of a ship, only God knows how a hole with a diameter of three and a half feet would be plugged. Several bold and successful attempts by the English from the sea have led to a fairly widespread belief that land batteries cannot defend against fleets that are much superior in terms of the number of cannons. One such attempt was made by Lord Duckworth in 1807. At that time, he passed through the Çanakkale Strait almost without any resistance and on February 20th, for the first time, an enemy fleet appeared before the walls of the Ottoman capital.

The Turks had so little thought that such a thing could be possible that their initial confusion was proportionately great. It is known that what prevented the Divan from agreeing to all the English demands was the influential activity of the French ambassador. Batteries appeared as if they sprang from the ground on the shores of Tophane and the Palace, while Çanakkale was quickly made ready for battle behind the English. Soon, the English ambassador Admiral did not know what his military success would be good for. Within eight days, Lord Duckworth considered himself fortunate to have been able to reach the quay of Bozcaada (Tenedos) again, even at the cost of losing two corvettes and almost all the other ships being damaged...

I must also mention a situation that is not at all suitable for ships to pass from the Çanakkale strait to the Marmara; throughout the summer, the north wind blows almost incessantly, and merchant ships often have to wait from four to six weeks to be able to go up the strait. Finally, if a south wind blows, it must be quite strong to overcome the strong current that is always southward in the Çanakkale strait. However, often the south wind blows at Kumkale but completely stops at the Nağra opening. If the artillery equipment in the Çanakkale strait is arranged, I do not think any enemy fleet in the world would dare to sail up this strait. It will always be necessary to land troops and attack the batteries to capture them. But this may not be as easy as it is said. Perhaps they can capture commanding points like the new and old fortresses with walls 40 feet high; but still, it is possible to defend within them for quite some time, as long as one has the will. Moreover, there is no hill dominating Kumkale and Sultan Hisar.

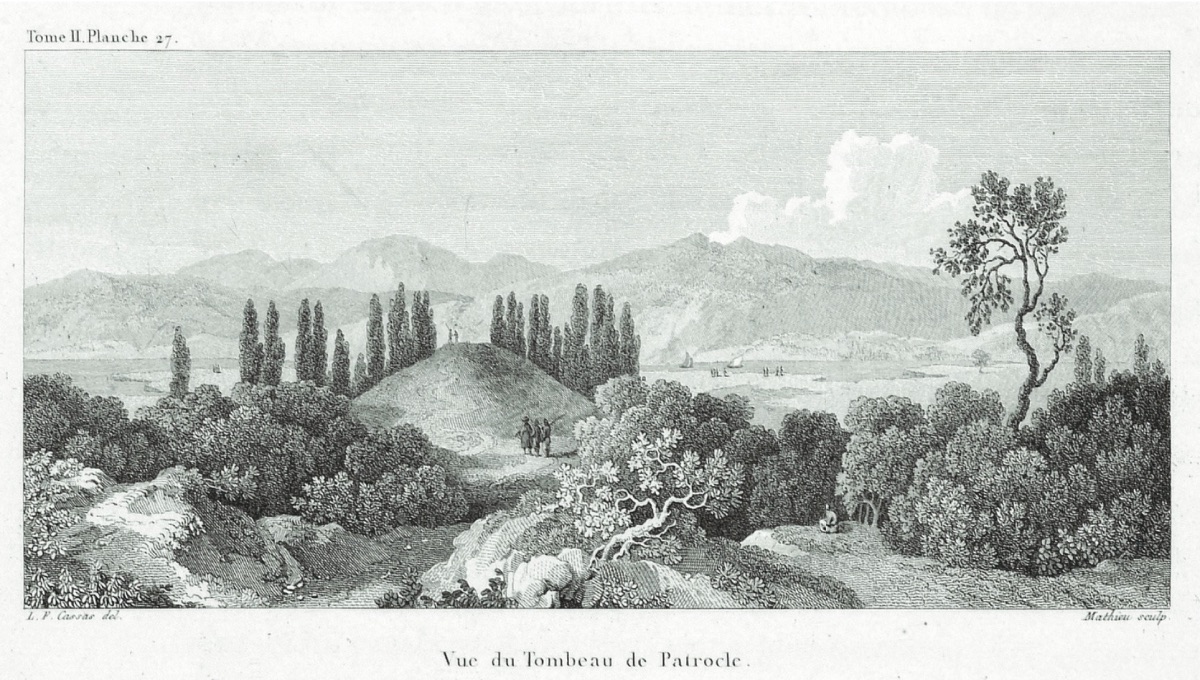

After this, I took a trip to the ruins of the city of Alexandria Troas, which was founded by one of Alexander the Great's commanders, Antigonos, to honor his master, and whose quay between Tenedos and the low Asian shore still provides a good anchorage for the largest fleets today. We passed by the tomb of Patroclus, from which I took an olive branch, and then proceeded towards the Cape of Sigeum along the desolate sandy shore where Pelides mourned the beautiful Briseis. This cape looks out over the magnificent sea and the harsh view of the islands, Gökçeada (Imbros), Samothrace (Thracian Samos), and behind it, Bozcaada (Tenedos) where the Achaean fleet was hidden. On top of a hill that looks as if it were piled up by human hands is a Greek village called Aya Dimitri. The tightly clustered houses of this village give it the appearance of a castle. Although I know that Pergamos (the name of the fortress of Troy) was not here but further inland, it amuses me to imagine that this village was the fortress where many people came and went, and that the heroes of divine descent perhaps did not live in better houses than these mud huts. This region is hardly cultivated, young camels graze on the high dry meadows, and the fields are adorned only by a few scattered oak trees.

As we arrived at a large Turkish village where we would spend the night, the sun set behind a mountain range. We went to the village headman, who greeted us hospitably: "Good evening. Welcome, you have come safely," he said. He left us his room, his bed, his house, and even offered me his own pipe. That day there was an earthquake. The first tremor was felt in the afternoon, but I did not feel it because I was on horseback, and I did not feel the second tremor at night because I was in a deep sleep. But towards morning, I felt myself shaking in my bed and woke up to the rattling of all the windows and doors. In Çanakkale, all three tremors were felt quite strongly.

The next morning, after passing through a valley with poplar, chestnut, and walnut trees, we saw the ancient walls of Alexandria Troas before us. These were made of enormous stone blocks 6-10 feet long and 3, often 6 feet thick, and stretched as far as the eye could see through the scrubland.

We advanced at least a thousand steps along this wall and found enormous stone ruins, granite columns, vaults once elegantly covered with hexagonal stones, and fragments of architraves and beautiful column capitals scattered across the plain. Suddenly, a ruin made of giant stones appeared before us. Its very beautiful, large arched gate defies all earthquakes and centuries. Seeing such a giant building in such a completely deserted wilderness evokes a sense of melancholy.

The Turks call this place Old Istanbul. They use sarcophagi as water troughs, their lids as bridges over streams, and the columns to make cannonballs for their stone-throwing cannons."