"We spent the entire day on the continental side of the strait, lingering near Assos, which with its beautiful ruins captivates artists and antiquarians. After a great struggle against the wind coming from the opposite direction, and after a long, peaceful sleep, we reached Baba Burnu (the ancient Lektos plateau R.A) on the morning of May 15 and saw the vast plains of Troas lined with tents belonging to Turkish soldiers as far as the eye could see.

In the afternoon, our sailboat anchored at Bozacada (Tenedos), where I disembarked for a few hours. From Bozcaada (Tenedos), I intended to go ashore (the distance is no more than six or seven miles) to see the ruins of Alexandria Troas, the much-discussed water sources, tumuli, etc., and then proceed to the Çanakkale (Dardanelles) forts, where the Sardinian captain would take me on board. I was told that I had to obtain a passport or a permit from the island's pasha and take an officer or a Turkish messenger with me. It was too late to visit the pasha, who had retired to his harem for rest and would not be available until the next day or could not be disturbed. Therefore, I went with my guide (a poor Greek working as the Austrian and Sarinia consul) to the Major or commander, the next responsible person after the pasha.

I found him in a wooden house that seemed about to fall apart, creaking and swaying with every step. When I entered, he was sitting in a small, round room with the captain and two officers of a Dutch warship anchored on the island. As he ate, three wind musicians and two drummers played music so loudly that it shook the house to its core. He gestured for me to sit beside him, while my assistant sat by the door; the music was not to be interrupted and continued for fifteen minutes until my ears nearly burst, though my head was pounding. After we all congratulated him and his musicians, I got down to my business. The Major watched silently. After some thought, he said that if I was determined to tour Troas, he would give me a permit and two or three officers. But he also wanted to leave me undecided by saying that neither the pasha nor he had enough power to protect me. He informed me that there were eight thousand military troops on the promontory where the plains of Troy were, that these undisciplined soldiers spread out irregularly over miles, came from the interior of Asia Minor, and showed little interest in foreigners and commanders. After expressing his regret over such issues, he kindly suggested that I could make my visit at a more suitable time when the Sultan did not have to send troops to Troas to protect the Dardanelles against the hostile actions of the Franks. Hookahs, coffee, and boxes of small cakes were served around, and as we left, the kind Major asked if I had any coffee, rum, or woolen clothes to sell at a cheap price: "I will pay for everything I take," he said. I told him I was not a merchant and unfortunately did not have such things. My explanations did not seem to meet his expectations.

Bozcaada (Tenedos), with its very important position in terms of the Dardanelles (Dardanelles), was guarded by a garrison of six hundred sailors coming from Istanbul (Constantinople). The fort was on the shore facing Troy; small and weak; only five usable small-caliber cannons; the walls, like all other forts built by the Turks I had seen, were of very ordinary workmanship. The Russian fleet destroyed the fort in 1770 and could do so again if they wished.

There is no export from the island except wine; we could not even find a piece of vegetable. The settlement is in a miserable state, with almost all of the approximately five thousand population being Greek and very poor. There is no regular unit, no significant disorder, but everything, though very miserable, is slowly getting on track: this is the ongoing happy change after the massacre of 1822.

There are no ancient monuments preserved on Bozcaada (Tenedos). I looked around carefully to find the not very significant remains that Dr. Chandler and other travelers saw in the town. They have all disappeared! People cause great destruction in a few years: the last five years of Sultan Mahmud's reign have caused a disaster far beyond the usual in terms of ancient works. Wherever a good stone or marble is found, if it is within a suitable distance to transport, it is taken to be used in the new buildings and pavilions he had built. Even the secularization of Phidias's (the famous sculptor of the ancient period) old work cannot save it; only the purse of a foreigner or a firman in the hands of an envoy can prevent this. When I returned to the deck, I saw that the captain, unable to make headway against the current, had anchored under the island to spend the night, like many other ships...

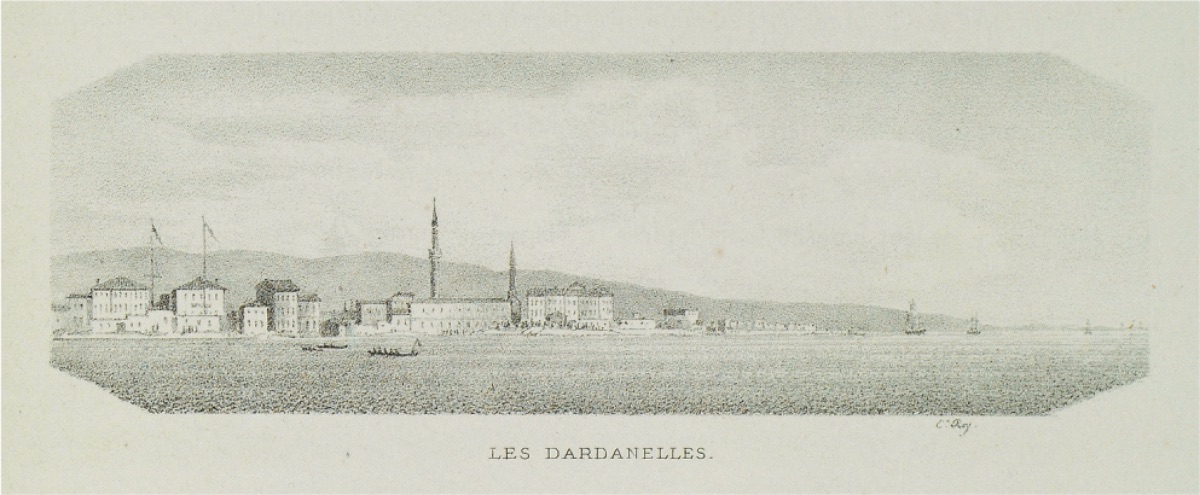

The next morning we started to move with almost no wind. We stopped on the Asian side to escape the current and slowly drifted toward the immortal shore. Zeybeks or irregular highlanders were gathered in crowds on the shore, looking at us as our small fleet passed by. Some were swimming in the sea, some were sitting cross-legged in front of the tents smoking hookahs, while others were dealing with horses and camels. They had small anvils between their knees, repairing weapons or making horseshoes with coal fires beside them... The next day, with the most favorable fresh south wind, we reached Çanakkale (Hellespont) and landed from the fort without any interference from the Turks. The Sardinian vice-consul who came on board at the Dardanelles informed us that, in addition to the regular garrison of artillerymen and sailors, three to four thousand irregulars had been gathering in groups since February at the site of the plains of Troy, causing constant disturbances and unrest, half-starved and without respite...

As we continued to make headway against the current with the support of a pleasant breeze, the courage and heroism of the unhappy lover Hero and the unfortunate Lord Byron came to mind. Swimming back from Abydos to Sestos from the Asian side to Europe is very difficult due to the currents. Outside Çanakkale (Dardanelles), with its dark green tall cypresses, gardens, olive groves, slender white minarets, and domed mosques among individually painted houses, the Dardanelles (Hellespont) did not meet my expectations...

Gelibolu is interesting as the first place in Europe of the rapidly expanding and equally disastrously ending empire of the Turks. The cheerful, quite old traveler Tournefort provides a good summary of the history here and the barbaric epics of the early Ottoman conquests. In the town, there is a mixed population of twenty thousand (recent travelers give the population as sixty thousand) consisting of Turks, Greeks, Armenians, and Jews. In trade, corn, wine, and oil are of great importance. Around the town, there are fertile gardens planted by Greeks, but beyond them is like a desert.

During my stay in Gelibolu, I saw for the first time those known as addicts (theriaki) or opium eaters. Although the use of this harmful drug generally leads to poisoning, I did not encounter anyone using it among the large Turkish population in Izmir or during my travels in Anatolia; nor did I see or hear of anyone using such a drug pill (apart from my own few attempts). It was for the first time in Gelibolu, at the entrance of a small tobacco shop next to the market, that I saw a Turk, in a trance-like state, chewing the madjoon spirit (opium). He was an old man with a white beard (the shop owner), sitting in front of a table or counter, with his hands and feet stretched out forward, his head fallen between his shoulders, his eyes staring motionlessly at a point."