Raczynski (1786-1845), a diplomat and politician from a Polish aristocratic family, undertook long journeys to the East, particularly to see ancient artifacts and explore the geographies mentioned in classical works. Raczynski's journey to Turkey began on July 17, 1814, from Warsaw with a large group, including artists. Continuing his journey by ship via Ukraine and Odessa, Raczynski and his entourage entered the Bosphorus on August 9. Having visited all the significant monuments and ruins in Istanbul, our traveler also made detailed observations about life and social conditions in Istanbul. He set out for Çanakkale on September 10, but due to a storm, he only managed to reach Lapseki with a delay. He then visited important ancient cities in the Çanakkale region. He examined in detail the geography of the Trojan Epics in the light of previous researchers. Raczynski's return was also quite challenging. Unable to cross the strait due to a storm, he returned to Istanbul by land from the Gelibolu coast, thus also visiting the Tekirdağ region. Although Raczynski reached Istanbul on October 9 and Odessa on November 5, he was quarantined due to cholera and could only return to his country on November 27. Like many European travelers of his time, his observations largely exhibit an Orientalist style, yet some detailed descriptions provide interesting insights into the year 1814:

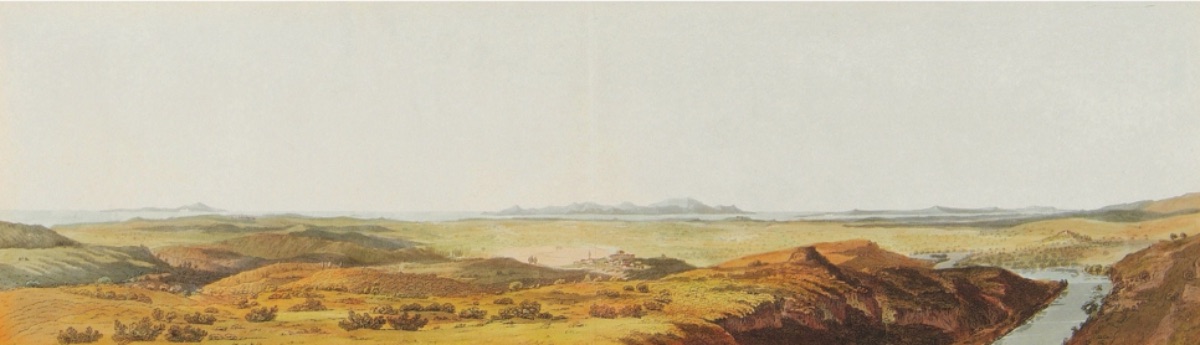

"On the morning of September 26, we set out early by boat along the Anatolian coast towards Yenişehir Cape. As dawn broke, the peaks of Ida appeared. The coast of Troy was gradually unfolding before our eyes.

This region, which we gazed upon from afar with impatience and longing, had attracted the attention of all civilized nations, aroused the curiosity of the enlightened, and despite traditions and religion, had been the scene of the development of political relations for three thousand years. When the light north wind died down towards noon, I steered towards the shore. From the land, I reached Yeniköy and then Yenişehir Village on Yenişehir Cape, where Greeks and Turks lived together...

After passing Yeniköy, there is a hill approximately 40 feet high by the sea. If I am not mistaken, Le Chevalier identifies this hill as the tomb of Nestor's son Antilochos. I bought an ancient bust found in the vicinity from a villager. The local people often find old coins, figures made of clay, marble, or bronze here. They know how to sell these ancient artifacts they unearth to Europeans, especially to interested Englishmen, at exorbitant prices...

We rode our horses along the battlefield of Homer's heroes, watching the peaks of Ida, and reached Pınarbaşı village, about 3 miles from the sea, where the fortress of Troy probably once stood...

Exhausted by the sun's heat, we returned to Pınarbaşı towards noon. From there, we went to the mansion of an Ağa who had a garden built where Skamandros originated and where Priamos' gardens once were. A few days earlier, someone from the household had found a bronze ring in the area. There were a few marks indicating an ancient inscription, unfortunately unreadable. I was fixated on the ring. I thought perhaps noble Priamos or beautiful Helena had worn it. I bought the ring for my brother to use as a token of love and fidelity.

The Ağa's mansion was a rectangular wooden building. His steward was Jewish and spoke beautiful Spanish. He welcomed us warmly. In the outer courtyard of the mansion, I saw many two-wheeled carriages resembling the ancient chariots on which victorious Roman commanders were taken to the Capitol from the streets of Rome and on which Homer's soldiers fought...

I had come here for research purposes. It was my fate to see the sources of Skamandros, which intrigue the reader of the Iliad and the archaeologist, emerging from among the willows and poplars near Pınarbaşı. According to the villagers, Skamandros had 45 sources. I could only see 18 of them. The others were very insignificant. It is reasonable to think that Troy was established on a hill near Pınarbaşı to benefit from these sources...

On the morning of September 27, we departed from the beautiful land watered by Simoeis and Skamandros and shaded by Ida, heading towards Çanakkale...

The strait widens north of İntepe, forming a bay on the Asian coast. Here, in 1401, French Marshal Bouicicaut, rushing to the aid of Byzantium with a war fleet of four parts, forced a Turkish fleet to retreat...

When the Turkish fleet was defeated at Çeşme in the 1770 war, Baron de Tott was asked by the Turkish government to increase the defense power of the Strait against a possible Russian fleet attack. The French engineer implemented his measures with great skill, considering the topographic situation. He placed heavy cannons on strategic capes on both the Asian and European sides. As is known, the current in the Dardanelles is so strong that ships coming from the Aegean Sea to Istanbul have to open all their sails to resist the current. The larger the surface area of the opened sails, the more terrifying the effect of the cannonballs and shells fired from the heavy cannons cast by Baron de Tott will be. If the equipment is slightly damaged, the enemy ship will inevitably be caught in the current and eventually fail under the fire of the coastal batteries. The neglect of these fortresses skillfully built by Baron de Tott allowed Admiral Druckworth to pass through the Strait in 1807.

We landed in Çanakkale around noon. A wealthy Jewish Russian consul hosted me. He obtained the necessary permission for me to see Çanakkale and the coastal batteries. The fortress was built in the shape of an elongated rectangle surrounded by stone and towers. The moat, approximately 40 feet wide (1 foot = 30.48 cm, R.A), was so shallow that one could easily cross it anywhere. A large caliber cannon was placed in the fortress.

The hospitable Russian consul gave a banquet attended by many merchants. The meal was prepared entirely in the Turkish style. A table was set on the ground. A shiny leather was spread over it instead of a tablecloth. The tableware included ivory spoons. As is known, Turks do not use forks. They tuck the knife they use at meals into their belts like their daggers in war.

The dishes were served in the following order in tin-plated containers: rice soup was followed by lamb meat, cut into small pieces with a broad knife by the host and offered to the guests. The meat was so well-cooked that it could be torn apart with fingers. Then came stuffed zucchini with yogurt. This dish, which the Ottomans generally loved, was inherited from their ancestors. Finally, eggs cooked with lemon in a pan and kebab were served... During the meal, I witnessed a Jewish merchant speaking beautiful Spanish with the consul, and I learned from the consul that he came from a Spanish family that settled in Çanakkale in the 17th century...

In the evening, I bid farewell to the consul and returned to our boat. We set sail and soon reached the cape where the ancient city of Abydos was located. Here, the width of the Dardanelles narrows to a few hundred fathoms. In 1807, batteries and fortifications were established here to protect Istanbul from the attack of the British fleet under the command of Admiral Duckworth...

On September 28, as I could not continue my journey against the north wind, I went to the Swiss consul, to whom I was recommended by his representative in Istanbul... According to the Swiss consul, the city of Gelibolu, with a population of 40,000, had 10,000 houses. The architecture of the houses was no different from what I had seen so far."