"We began our walk towards ancient Ilion with the accounts of Homer and Kauffer and the map made by Lechevalier. At first, we will try to make a decision by seeing all the interesting places and making our own observations. The scenes described by the poet about these places will be brought to light again, then re-examined with scrutinizing eyes; it will be tested whether the nature of the soil here aligns with the ancient accounts and whether the accounts of new travelers align with the nature of the soil. If these similarities can still be seen despite the ravages of time and barbarians, and if there is indeed a correspondence between the Iliad texts and geography; then Homer's accounts can be accepted as a true depiction of the entire environment. Thus, the views of those who object to the existence of ancient Ilion based on the contradictions in the poet's accounts would be completely invalidated.

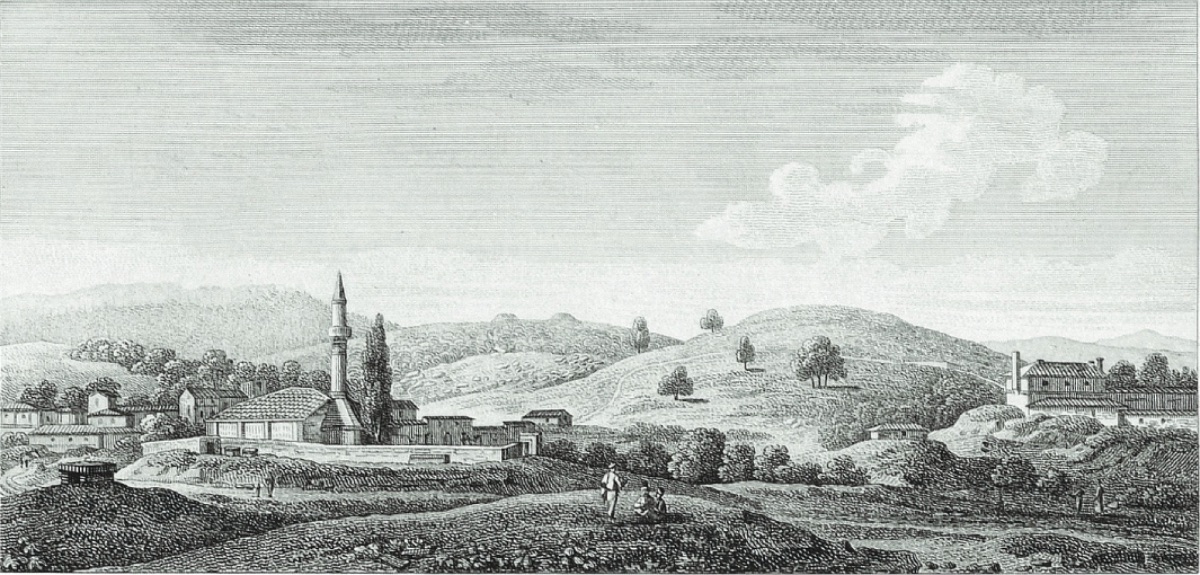

On the European side of the Dardanelles, halfway along the road from the first fort to the last fort, behind a hill cut by a deep valley, there is said to be a pasha's farmhouse. The name they give to this place is Sogan Deresi, meaning onion valley. Near here, a man-made burial mound rises. After a two-hour sea journey, you reach the outermost fort on the European side; from here, you almost cross the strait towards Kumkale on the opposite side.

This place takes its name from the sands carried here by the north wind, partially blocked by natural rocks and partially by the castle walls. If not removed annually, the sand dunes piled on the visible side of the castle could almost rise above the castle walls. After this, the usual tour continues on horseback. Facing the sea, you see the elevation of the Rhoeteon settlement on the right and the New City cape where the Sigeion settlement is on the left. The Greek fleet and harbor were situated between these two. In the middle were the ships and tents of Agememnon, king of the Greek peoples; cunning Odysseus; and on either side, the brave Ajaks and godlike Achilleus. But on which side did Telamon's son and Peleus' son stand? The views of those who previously visited here, accepting the burial mound next to the Rhoeteon hill as Ajaks' tomb, from Strabon onwards, but also by Cretan Dictys and Pausanias, certainly do not lose their validity regarding the presence of his tomb and his tent on the same side. Thus, we also see that Homer was right.

...

Now, we return to the place where the Sigeion elevation is to search for the burial mounds of the other Greek commanders, swift-footed Achilleus.

The natural bay, almost covered by sands, Dark Harbor (dark harbor), and then the coastal shrubs prevent us from proceeding directly.

After returning from the wooden bridge over the Menderes and reaching Kumkale, we proceed along the windy seashore with the burial mound overlooking the sea from the hill where Chyses failed to take revenge on Phiobos with his terrible bow, as the arrow made a sound just a step away.

When Patroklos was buried, the Argives went to Ida to gather oak trees for the funeral pyre and decided to pile them next to Achilleus' tent, where he planned to make a large burial mound for himself and Menoetes' son. Because while Achilleus lay on the sea shore battered by the waves at night, Patroklos appeared in his dream. He asked that their bones not remain separate in the tomb. After honey and oil were poured on the woodpile; when the fire fed with sacrificed Trojans, sheep, bulls, horses, and dogs was extinguished with wine; Achilleus ordered a burial mound to be made from the remaining ashes. But he wanted it to be a small burial mound so that the remaining Argives could make it larger and wider. This burial mound, facing the Dardanelles (Hellespont), is the largest and widest, a hundred steps high (only a hundred steps were the remnants of the ashes).

Here, the ashes of the bravest, most loyal soldier of the Greeks are kept in a container. The ashes of Achilleus and his friend Patroklos are mixed together and kept in the same container with their comrade Antilochos' ashes in a separate place. But centuries after their deaths, dark clouds loomed over the fate of the heroes' ashes. Like Ajaks' tomb, Achilleus' tomb was also opened. The first was opened by Antonius, the second by Count Choiseul Gouffier, breaking the ceremonial silence of the tomb.

Jewish Salomon Ghormezzano secretly conducted excavations in Çanakkale (Dardanelles) and sent the findings to the Count and sold some sample pieces he kept to traveler Heinrich Hope. According to Ghormezzano's accounts, there was no dome in the tomb; there was a cubic space four feet large surrounded by a wall plastered with mortar as hard as stone, a hand's width thick; unfortunately, its surface collapsed either due to the weight of the soil or the carelessness of the diggers. Everything inside, except for a broken vase, was covered by the wall.

...

Every step we take reminds us of another event witnessed by these shores. The Trojans, chased by Achilleus with great fury, take refuge here; groups of soldiers and horses turn around the harbor, gasping for breath. Achilleus hides his spear among the tamarisk bushes here..."